Hey all you people out there. It seems that I’m not the only one to have noticed the crazy resemblance between that one Egyptian statue at the Field Museum and … oh … the most famous entertainer in the history of the world, Michael Jackson. The press also caught wind of the same likeness early this month and the web has been lit up with articles and blog posts. If you want to check it out yourself, I’ve put together a collection of many links at ancientartpodcast.org in the Additional Resources section under the blog post “Ancient Egyptian Michael Jackson look-alike.”

Hey all you people out there. It seems that I’m not the only one to have noticed the crazy resemblance between that one Egyptian statue at the Field Museum and … oh … the most famous entertainer in the history of the world, Michael Jackson. The press also caught wind of the same likeness early this month and the web has been lit up with articles and blog posts. If you want to check it out yourself, I’ve put together a collection of many links at ancientartpodcast.org in the Additional Resources section under the blog post “Ancient Egyptian Michael Jackson look-alike.”

My wife and I went to the Field Museum last weekend to see the “Pirates” exhibition, and while we was there I took a few new photos of the Egyptian statue. Added bonus, we got our names stamped in Egyptian hieroglyphs, but I was a jerk and made them redo her name, because they spelled it wrong.

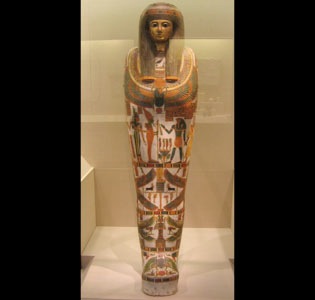

Like the gallery label in the Field Museum says, the statue is of a woman from the New Kingdom. That’s pretty vague, but if you look at it closely, you’ll notice that the facial characteristics and headdress bear some resemblance to the topic at hand in recent episodes, the Amarna period. Those sharp almondine eyes, deep eyelids, large full lips, high cheekbones, and exaggerated eyebrows all indicate the influence of the Amarna period following the reign of the heretic king Akhenaten. Plus the wig favors the fashion of the time.

Last time in episode 22, “Nefertiti, Devonia, Michael,” in our discussion of Lorraine O’Grady’s contemporary works Miscegenated Family Album and Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline, we briefly briefly talked about the family of Akhenaten and Nefertiti and touched on the line of kings following Akhenaten. It gets a little confusing late in Akhenaten’s reign. Did Nefertiti rule alongside him as coregent? Was there another male king on the scene? Did one of Akhenaten’s daughters assume the throne for a while? How many kings were there between Akhenaten and Tut? These questions continue to be debated, as can be seen in the latest issue of KMT magazine, the Fall 2009 issue, volume 20, number 3, in Aidan Dodson’s article “Were Nefertit & Tutankhamun Coregents?” Your head can really spin around if you think too hard about this. It’s like trying to solve a jigsaw puzzle without the picture on the box and only half the pieces.

Looking at what we do have, though, we see evidence of a somewhat turbulent transition from heretical Atenism back to orthodoxy, but it’s not a complete return. The Amarna period has a lasting impact on Egyptian art, giving rise to what’s sometimes dubbed the post-Amarna period, or more romantically the “legacy of Amarna.”

You might be familiar with this all-too-famous throne from the tomb of King Tut, which can be yours now for only $895 plus $39 shipping and handling direct from SkyMall. The original of this magnificent work of Ancient Egyptian artistry is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. There are countless spectacular things about it, but one interesting nuance to zero in on is the inscription. The chair must have been produced very early in the reign of King Tut. We can tell because he’s referred to by his early throne name, Tutankhaten, with his wife Ankhesenpaaten, third daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. About a year into his reign, Tut changed his name from Tutankhaten to the more familiar Tutankhamun, which means the “living image of Amun,” and his queen changed her name from Ankhesenpaaten to Ankhesenamun, or if you’re Boris Karloff, that’s “Ankhsenamun” (1). Of course, at the time, Tut was only about 10 years old, so the notion that he made any decisions on his own other than which toy to play with today might be a little far fetched. More likely the name change was imposed on the boy king by his vizier Ay and other advisers like general Horemheb to win favor with the bitter and previously disenfranchised temple of Amun. “No, really, we were on your side the whole time. Yeah, that’s the ticket!”

Stylistically, the decoration of the chair also shows a strong entrenchment in the Amarna period, not only with the subject matter of the solar disk Aten shining down on the royal couple, but in the figures themselves, with their long slender limbs, sharp almondine eyes, large heads, elongated torsos, and cute little paunches. These characteristic Amarna features gradually soften in the arts, becoming less pronounced as time marches on. Some works of art well into the following 19th dynasty, the time of those bijillion Ramses’s, continue to show strong vestiges of the Amarna style, which we will examine in a minute, but one final note that deserves recognition is the coloration of their skin.

King Tut is represented with the customarily dark skin of Ancient Egyptian men, but so is his queen. Egyptian women are traditionally shown with lighter skin than men. The typical explanation for this is that men worked outdoors all day, so they had tan skin, whereas women worked indoors all day, didn’t tan as much, and are therefore traditionally shown with fairer skin. That argument is also usually put forth against skin color as an indicator of heredity. Well, permit me to get a little cynical, but that’s a prime example of art historical chauvinism getting in the way visual interpretation. Translation: look before you leap. There are many works of art from throughout Egyptian history where it’s safe to interpret racial type being expressed through skin color among other features. God forbid the Egyptians practiced mixed marriage as far back as 2600 BC, as evidenced in the statues of Rahotep and Nofret from the 5th Dynasty in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. What continues to hold public interpretation back from a more realistic, diverse perspective of the Ancient Egyptians are the sweeping blanket statements that often find their way into the press, along the lines of “[Ancient] Egyptians are not Arabs and are not Africans despite the fact that Egypt is in Africa” (2). The issue’s not black or white. So, was Ankhesenamun a tomboy, spending more time outdoors than a proper young Egyptian lady should, or were she and Tut both of a more southern Egyptian heritage, closer to Nubian? Well, that’s a can of worms we don’t have time to get into, but if you want a nice synopsis of the whole issue, check out the 20-year-old article by Frank Yurco “Were the Ancient Egyptians Black or White?” in the September/October 1989 issue of the Biblical Archaeology Review or BAR. You’ll find a link to the full text article in the bibliography at ancientartpodcast.org.

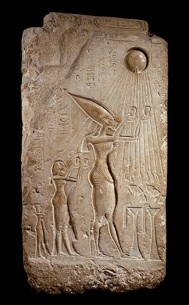

And then from some 20 to 100 years after the reign of King Tut comes this Lintel and Cornice from the Tomb of Iniuia and Yui at the Art Institute of Chicago. The dating is a little conflicted. The Art Institute dates the lintel to 19th dynasty during the reign of Ramesses II, 1279-1212 BC, but most scholarship seems to peg Iniuia and Yui to the reign of Horemheb, 1323-1295 BC. A lintel is simply the top of a doorway. The cornice here refers specifically to the characteristic Egyptian cavetto cornice with torus molding. The cavetto cornice is the classic, striped, flaring top section of a doorway and the torus molding is the protruding rounded ledge between the cornice and figural decoration. The cavetto cornice and torus molding both likely have their roots in traditional reed vegetal architecture translated into stone.

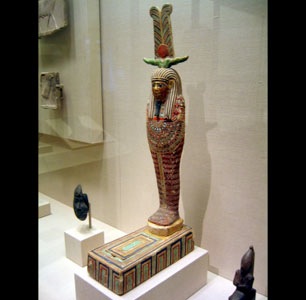

This piece was originally located above a doorway in the tomb of Iniuia and Yui from Saqqara. We don’t know a whole heck of a lot about them. Iniuia is the husband and Yui is his wife. In the inscription on this fragment, Iniuia is referred to by the title “Overseer of the Treasury of Silver and Gold of the Lord of the Two Lands.” At some later point in his career, he gets the titles “Overseer of the Cattle of Amun” and “Royal Scribe and Chief Steward of the Great Palace” and Yui is referred to as the “Lady of the House, the Chanteress of Amun,” which we see on their darling little double shawabty coffin lid from the MFA in Boston, which I had the pleasure of seeing in person for the first time just a couple weeks ago and snapped this lame cell phone picture.

What we are really interested in with the lintel, though, is the Amarna influence. We see Iniuia and Yui supplicating before Osiris and Isis, their hands raised in prayer, so this is clearly after the Amarna period, since the orthodox gods have been reintroduced. But look closely at Iniuia and Yui. Notice their slender limbs, elongated torsos, protruding chins, pronounced cheekbones, sharp almondine eyes, and their little potbellies. Note also how the artists has seemingly rendered a straight line from the tips of their noses to the peak of their foreheads. These are all very distinctive traits developed during the Amarna period. Even upwards of 50 years or more after the reign of the heretic king Akhenaten, after the radical transformation of Egyptian art, religion, and society, then after the rampant, vehement, passionate movement to eradicate all traces of the previous order and restore Egypt to its orthodox religious traditions, we still continue to see a lasting artistic influence of the monumentally influential Amarna period.

Thanks to all, who have been sending feedback. I appreciate you taking the time and making the good suggestions. If you want to be part of the cool crowd too, you can give feedback on the website and fill out a fun little survey. If you have any questions you’d like me to discuss in future episodes, you can also email me at info@ancientartpodcast.org. You can comment on each episode on the website or on YouTube. And if you like the podcast, why not share the love with some iTunes comments? It helps to get the podcast noticed. Lastly, you can follow me on Twitter at lucaslivingston. Thanks for listening and we’ll see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2009 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

Footnotes:

1. Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen. Exhibition catalog edited by Rita E. Freed, Yvonne J. Markowitz and Sue H. D’Auria, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts in association with Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown, and Co., 1999, page 180.

2. “Hawass Says That Tutankhamun Was Not Black.” Touregypt.net. 2007-9-26. Retrieved 8-18-2009.

Image Credits

1. Statue head of a woman, limestone, New Kingdom, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago (31713), photo by Lucas Livingston.

…

1. Comparison of Field Museum Statue head of a woman and Statue of an unknown Amarna-era princess. New Kingdom, Amarna period, 18th dynasty, ca. 1345 BC Egyptian Museum (21223), Berlin, photo by Keith Schengili-Roberts, 15 Dec 2006.

2. Chair of Tutankhamun, 18th dynasty, Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

3. Chair of Tutankhamun (detail), 18th dynasty, Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

4. Chair of Tutankhamun (detail), 18th dynasty, Egyptian Museum, Cairo, photo by Richard Seaman.

5. Chair of Tutankhamun (detail), 18th dynasty, Egyptian Museum, Cairo, photo by Pataki Márta.

6. Chair of Tutankhamun (detail), 18th dynasty, Egyptian Museum, Cairo, photo by Jerzy Strzelecki.

7. Golden Mask of Tutankhamun, Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

8. Cartouche of Tutankhamun.

9. Cartouche of Tutankhaten.

10. Boris Karloff as Imhotep from The Mummy, Universal Pictures, 1932.

11. Decorated Balustrade Fragment, Amarna, Great Palace, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, 1353-1336 BC, Crystalline limestone, Egyptian Museum, Cairo, JT 30/10/26/12.

12. Lintel and Cornice from the Tomb of Iniuia and Yui, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18 or 19, reign of Horemheb (1323-1295 BC) or Ramesses II, (c. 1279-1212 B.C.), The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Henry H. Getty, Charles L. Hutchinson, Robert H. Fleming, and Norman W. Harris, 1894.246.

13. Lintel and Cornice from the Tomb of Iniuia and Yui, photo by Lucas Livingston, 21 August 2009.

…

1. Wall Fragment from the Tomb of Amenemhet and His Wife Hemet, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12 (1976-1794 BC), The Art Institute of Chicago, Museum Purchase Fund, 1920.262.

2. Scene depicting the procession of funerary offerings from the tomb of Amenemhet, senior officer during the reign of Thutmose III, Dynasty 18 (1479-1425 BC) from The Yorck Project: 10,000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH.

3. Head of Queen Tiy, Egyptian Museum, Berlin.

4. Shawabtys of King Taharqa, Nubian, Napatan Period, reign of Taharqa, 690-664 BC, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

5. Statues of Rahotep and Nofret, Dynasty 4, reign of Sneferu (2575-2551 BC), Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

6. Ka statue of Rahotep, Dynasty 4, reign of Sneferu (2575-2551 BC), Egyptian Museum, Cairo, photo by Jon Bodsworth, 10 December 2007 (egyptarchive.co.uk).

7. Ka statue of Nofret, Dynasty 4, reign of Sneferu (2575-2551 BC), Egyptian Museum, Cairo, photo by Jon Bodsworth, 10 December 2007 (egyptarchive.co.uk).

8. Temple of Philae, Description de l’Egypte, Ile de Philae – A. vol. 1, pl. 18, 1809.

9. Lid for double shawabty coffin [of Iniuia and Yui], New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Horemheb (1323-1295 BC), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William Francis Warden Fund, 1977.717.

10. Lid for double shawabty coffin of Iniuia and Yui, photo by Lucas Livingston, 12 August 2009.

11. Bust of Queen Nefertiti, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten (1351-1336 BC), Egyptian Museum, Berlin, photo by Magnus Manske, 28 December 2005.