41: Egyptian Art Doesn’t Change over Time

40: Akhenaten was the World’s First Monotheist

39: Tombs Depict Scenes from Daily Life

38: Egyptians Were Obsessed with Death

37: The Pyramids Were Built By Slaves

36: The Orion Mystery

35: The Lotus as a Narcotic or Aphrodisiac

30: Karnak II

Welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. This is Lucas Livingston, the peanut butter to your jelly on our ancient journey. Last time in episode 29, “Karnak,” we just scratched the surface or strolled the causeway, as it were, on our exploration of Egypt’s largest temple complex. In this episode, we’ll delve deeper into the precinct of Amun at Karnak, deciphering ancient imagery on the walls, reenacting an ancient festival, and breathing new life into the silent ruins.

Welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. This is Lucas Livingston, the peanut butter to your jelly on our ancient journey. Last time in episode 29, “Karnak,” we just scratched the surface or strolled the causeway, as it were, on our exploration of Egypt’s largest temple complex. In this episode, we’ll delve deeper into the precinct of Amun at Karnak, deciphering ancient imagery on the walls, reenacting an ancient festival, and breathing new life into the silent ruins.

When we were last together, we wrapped up in the forecourt of Karnak between the first and second pylons looking at the unfinished columns and the leftover mud brick scaffolding of the first pylon.

Just beyond the forecourt and second pylon is the Great Hypostyle Hall consisting of 134 papyrus-shaped columns. A “hypostyle hall” is a large room with a flat ceiling supported by columns. This space and much of the temple were originally roofed. The center 12 columns with open papyrus capitals are taller than the surrounding 122 columns, forming a section where the roof was elevated above the rest, connected by windows to let in some natural light. That technique is called clerestory lighting and it’s a common feature to Egyptian, Roman, and later Christian sacred architecture.

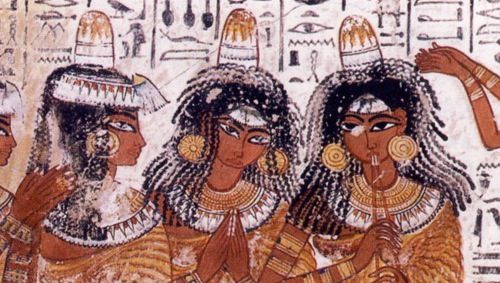

The decoration on the walls and columns in the hypostyle hall depict ritualistic imagery, offerings of the kings to the gods, and the procession of the sacred barque–that’s B-A-R-Q-U-E–a fancy-looking model boat that held the statue of the god. On the exterior walls of the hypostyle hall and much of the rest of the temple, we see battle scenes commemorating Pharaoh’s military victories over the enemies of Egypt. Occasionally it’s an attempt at history, but more often than not it’s a publicly accessible, propagandistic symbol of Egypt’s subjugation and authority over foreign lands and hostile forces of chaos. A fairly common motif is the larger-than-life Pharaoh grabbing a throng of enemies by their hair, ready to bash their heads in with a mace. Here’s Sety I, for example, father of Ramses the Great. Notice all those little grooves where the stone has been slowly carved away by worshippers. This practice started in ancient times and continued well after the temple had ceased religious activity. Much in the same way that Ancient Egyptian mummies would get pulverized and mixed with various ingredients for magical and medicinal concoctions, visitors to Ancient Egyptian temples like Karnak similarly recognized the temple’s magical power and sought to take home a little bit of that power in a powdered form. [1] So on the outside you get big political imagery of Pharaoh smiting enemies and on the inside you get religious imagery pertaining to the action taking place inside the temple and on festival days.

Another interesting thing about this relatively common depiction of Pharaoh smiting the enemies of Egypt is that they’re quite clearly depicted with frontal faces. It’s exceedingly rare to have a frontal face in Ancient Egyptian two-dimensional art. Back in episode 9 of the podcast, “Walk Like an Egyptian”, we touched on this phenomenon with the Mummy Case of Paankhenamun. The conventions of Egyptian artistic doctrine don’t apply here in the case of depicting foreigners. It’s not that the Egyptians didn’t know how to render a frontal face. Case in point. Rather, it’s that the complex relationship of state art, hieroglyphs, and Ma’at (cosmic world order and philosophical truth) limit the use of a frontal Egyptian face in painting and relief carving.

There’s one frontal face that’s relatively common in Egyptian art, which we see here on the obelisk of Pharaoh Tuthmosis I. It’s part of a Hieroglyphic inscription. This common hieroglyph is the preposition “on” or “upon.” So, you might be tempted to say, “See, look here. The frontal face is abundant in Egyptian two-dimensional art,” but it’s important to note that this is writing. It’s language. And even though I’m constantly emphasizing that hieroglyphs and art are inextricably related, sometimes writing is writing and art is art. This hieroglyph got its 15 minutes of fame not too long ago with President Barack Obama’s visit to Egypt back on June 4, 2009. He’s actually quoted as having pointed at that same hieroglyph inscribed on the walls of the Tomb of Qar at Giza and exclaimed, “That looks like me! Look at those ears.” Now, just how many presidents of the United States could express some sort of personal identification with an African nation? Huh?

As you go deeper into Karnak temple, the rooms gradually become smaller, the ceiling lower, and the floor slightly elevated. Think of it like an obelisk lying on its side: a wide base at the front of the temple, gradually tapering to a point at the head or what’s called the “naos,” where the statue of the god Amun was kept. Only a few elite priests were permitted to enter the naos, to clothe and cleanse the god. On certain festival days, the image of the god would be carried out of the naos on his barque shrine, that fancy model boat I already mentioned. Probably the most anticipated festival at Karnak was “the Beautiful Feast of Opet,” held annually during the inundation season. The Opet festival was a celebration of the Nile flood and its symbolic fertility as people across Egypt began planting their crops. The image of the Amun was carried through the temple as everyday Egyptian gathered around gawking at the god. If you look around the Great Hypostyle Hall, you’ll see funny-looking images of a bird with human hands raised up in adoration. That bird’s the Egyptian hieroglyph for “rekhyt,” which was the Egyptian word for themselves, the Egyptians. It’s thought that that glyph indicated to the people where they were allowed to stand during the festival. [2] There’s also this nifty little alabaster block decorated with images of bound, captive foreigners and bows. They represent the “nine bows,” Egypt’s enemies, although the actual number and national identity varies. It’s thought that this block was a rest stop for the priests to place the barque of Amun on its sacred procession. [3] So by placing the barque of Amun on top of the nine bows, the Egyptians were making a symbolic statement of political dominance over its enemies. A very well known representation of the nine bows is found on the sandals of King Tut, so with every step, he was treading over his enemies. The barque’s journey during the Opet festival continued along the south axis, out of the temple, around the sanctuary of Mut and south along the avenue of sphinxes to Luxor temple. After hanging out there for a while, it was brought back to Karnak, at times on land and at times along the Nile.

The relationship of land to water plays a big role in the architectural symbolism and programmatic vision of Ancient Egyptian temples. One interpretation of Egyptian temple architecture is that it models the creation of the universe, according to the popular Theban cosmogony. According to one tradition, the cosmos began as the primeval swirling waters, Nun. From this infinite ocean emerged a mound of earth where a single lotus blossom flowered. Within that flowering lotus was born the infant god Nefertem, and from his tears all the creatures of the world were formed. There are oodles of variants to this story as different cults rise to prominence and get folded into the mythology, but regardless of the fine points, the Egyptian temple is often seen as embodying the idea of creation from the primordial swamp. The rise in elevation of the floor from the temple entrance to the naos might reflect the primeval mound of earth, a little bit of cosmic order in an otherwise chaotic watery void. Similarly, the Egyptian hieroglyph for cosmic world order, the taming of natural chaos, is a stylized mound or the pedestal upon which the image of a god would stand, ma’at, which we’ve already encountered back in episodes 2, “Mummy Case of Paankhenamun”, and 9, “Walk Like an Egyptian”. Even more to the point, the columns decorating the many courts and halls of Egyptian temples were shaped to represent a variety of lotus, palm, and papyrus plants found along the Nile, having found their origin in the primordial swamp. Temple walls, much like tombs, were also sometimes decorated with marsh scenes. And to bring it all home, there’s evidence and testimony through royal inscription that temple forecourts were actually flooded now and again by the Nile’s annual inundation, which would have tied in beautifully with the temple as a concrete manifestation of the force of creation … well, not concrete, mostly limestone or sandstone. Yeah. [4]

So, there’s a lot going on in Karnak and other Egyptian temples. Even today, in their somewhat ruined state with sun-bleached walls, fragmentary sculpture, and eroding inscriptions, these mansions of the gods offer up a very palpable, if not mystical and spiritual experience of one of the greatest civilizations of the ancient world.

Don’t forget to visit ancientartpodcast.org for the full transcript, image gallery and credits, and additional resources to this and other episodes of the podcast. If you like the podcast, how about leaving an iTunes comment. Loves my iTunes comments, and it helps get the podcast noticed. I also appreciate the feedback on YouTube, and if you have any questions or comments or just want to say hi, you can email me at info@ancientartpodcast.org or get in touch with the feedback form at ancientartpodcast.org. You can friend the podcast at facebook.ancientartpodcast.org and follow me on Twitter at lucaslivingston. Alright, it’s been fun and I’ll see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2010 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[1] Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000, p 62, 99.

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid. p 157-8.

[4] Baines, John. “The Inundation Stela of Sebekhotpe VIII,” Acta Orientalia 1974, pp. 39-54.

29: Karnak

Welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast, your guidebook to the art and culture of the ancient Mediterranean world and beyond. I’m your friendly traveling companion, Lucas Livingston.

Welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast, your guidebook to the art and culture of the ancient Mediterranean world and beyond. I’m your friendly traveling companion, Lucas Livingston.

A few weeks ago, I had the fantastic opportunity to travel to Egypt and Jordan as a study leader through the Art Institute of Chicago. It was a great trip and I met some wonderful people. A big shout out to our intrepid travel director K.C. for her tireless effort. And even though most of the destinations we visited during the trip were thousands of years old, it sure seemed like a lot had changed since the last time I had been to the pyramids of Giza, Karnak and Luxor temples, the Valley of the Kings, and the mortuary temple of Pharaoh Hatshepsut at Deir el Bahri. A lot has also changed technologically since the last time I was there back in 1997; in particular with 35 mm film giving way to digital photography, encouraging wanton abuse of photographic hysteria. If you’re not already a fan of the Ancient Art Podcast on Facebook at facebook.ancientartpodcast.org or if you don’t follow me on Twitter at LucasLivingston, you might not yet have seen the hundreds of photos I uploaded from the trip. Well, head on over to either or and check them out.

Or to keep it really simple, go to ancientartpodcast.org and click on “Resources” to see links to the photo gallery and an interactive Google map with the geotagged photos. As an extra bonus there’s also a link to interact with the photos in Google Earth. So check it out.

My visit to Egypt and Jordan provided me not only with plentiful imagery, but also with copious fodder for the podcast. I thought a good launch pad would be an introduction to the amazing Karnak temple from Ancient Egypt. There’s so much to explore at Karnak that we’ll probably need a couple episodes here. This episode will give us an orientation in and around the temple. We’ll explore its grounds and layout, some of the architecture and history, and the different divinities revered at the sacred site. In the next episode, number 30, we’ll look a bit more closely at some of the decoration, the spiritual and political function of the temple, and the overarching philosophy and symbolism of Ancient Egyptian temple architecture in general.

Karnak is located in Upper Egypt, which means southern Egypt, because it goes by elevation, not latitude. Karnak, Luxor, the Valley of the Kings, and so many of Egypt’s other famous monuments are all clustered together in an area where the Nile makes a sharp bend around a relatively mountainous region. This is location of the ancient city of Thebes, given that name by the Greeks after the Greek city of the same name. The Ancient Egyptian name for Thebes was Waset. The name “Karnak” comes from the nearby modern village of the same name, as does the name of the nearby temple Luxor (al-Uqsur, meaning “The Palaces”). To the Ancient Egyptians, though, Karnak was known as Ipet isut, meaning “The Most Select of Places.” [1]

Karnak was more or less under continuous construction from the Middle Kingdom through the Roman era—that’s like 2000 years! The most ancient sections of Karnak in the deepest recesses of the sanctuary date back as far as Senusert I of the 12th dynasty, who ruled from 1971-1926 BC. The greatest period of construction and expansion was during the New Kingdom, around 1550-1307 BC. Nearly all the New Kingdom pharaohs left their mark on Karnak in some way or another.

Karnak is comprised of three main temple precincts dedicated to different gods. The largest precinct in the center is dedicated to Amun, or more properly Amun-Ra, after the two gods became syncretized. Within that precinct are many shrines, chapels, and subsidiary temples dedicated to different gods and pharaohs, including of course the Great Temple of Amun. To the north is the precinct of Montu, the falcon-headed Theban god of war. Montu was especially popular during the Middle Kingdom, which we see reflected in the names of the 11th dynasty kings Mentuhotep I, II, and III. Mentuhotep II, who ruled from 2061-2010, is the fellow who built his mortuary temple nestled in the foothills of the western mountains at Deir el Bahri, where Hatshepsut later build her famous mortuary temple modeled heavily after Mentuhotep’s, but we’ll save all of that for another episode of the podcast. South of the precinct of Amun connected by a long path or avenue lined by ram-headed sphinx statues lies the precinct of the goddess Mut, wife of Amun and the divine mother to the reigning pharaoh.

The avenue of sphinxes jogs around the temple of Mut and then continues roughly southward lined by human-headed sphinxes all the way to the Temple of Amun at Luxor. Over the years, the city of Luxor was built up on top of the avenue of sphinxes, but there’s a massive project underway today to excavate and reconstruct the avenue of sphinxes, reconnecting the ancient complexes and displacing lots of modern day residents. So you can imagine it’s been kind of controversial.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the temple to the god Khonsu, which lies within the precinct of Amun. Khonsu or Khons is the son of Amun and Mut, so you have a nice family gathering here at Karnak, which makes a lot of sense, since temples were considered to be the mansions of the gods. So Karnak as a whole is a magnificent estate with different buildings, rooms, and wings dedicated to the divine family of Thebes. The Theban pantheon and theology has many layers of complexity on top of that, but that’s a simple perspective.

Flanking the southern side of the Amun temple at Karnak is a fantastically large open-air museum of architectural fragments covering about as much ground as the temple itself. The collection is comprised mostly of blocks that were discovered being used as filler inside the temple pylons. The pylons are those massive blocky gateways so characteristic of Egyptian architecture. Throughout the history of Karnak, not only do we see continuous expansion and construction, but we also have constant renovation and demolition to make way for what were in their day new construction projects. If an earlier king’s addition to Karnak got in the way of a later king’s plans, it was not uncommon to demolish the earlier section, and it was certainly a cost saving measure to reuse that stone, which had already been nicely quarried and shaped, which today would help you earn credits toward LEED certification.

The temple of Amun is constructed along two primary axes; one running perpendicular to the Nile and the other running parallel. The perpendicular axis is generally designated east-west and the other north-south, but the temple is not actually orientated precisely along the cardinal axes. In general, however, it was common for Egyptian temples to be orientated east-west. Many of the western Theban temples on the opposite side of the Nile face east towards the rising sun and the river, while Karnak faces west, again towards the river for one for the very practical purpose of accessibility by boat. The first pylon is about 540 meters from the Nile today (in American units, that’s about 6 football fields), but in its day there was quay or a water way connecting it with the river. All in all, the temple of Amun is comprised of 10 pylons dating from the 18th dynasty through the 30th dynasty. While construction jumped around from place to place within the temple, the pylons generally radiate outward chronologically. So the first pylon where all tourists today enter is the latest from the 30th dynasty, the second pylon is older (late 18th-early 19th dynasty), and so on.

Between the first and second pylons is an open-air courtyard. What’s neat here is that this space was outside the temple proper in the New Kingdom, so you can see some sphinx statues here that were originally part of the avenue of sphinxes connecting to the Nile. You’ll also find some unfinished columns and the massive mud-brick scaffolding that was never removed after construction of the first pylon was halted. I think it’s really interesting to see evidence like this revealing the history and development of Karnak. It breathes a little life into the ancient stone, betraying that there was frequent expansion and renovation. It’s easy to visit Karnak today and take it for granted that we’re looking at a frozen snapshot in time, but that’s not the case. As we walk through this ancient complex, we’re treading across more than 100 generations of continuous occupation, development, devotion, and human achievement.

So, there’s a tight little introduction to Karnak and Ancient Egyptian temples. I hope you’ll tune in to the next episode, where we’ll go deeper into the temple, exploring the carvings on the walls, their meaning and symbolism. We’ll recreate an Ancient Egyptian festival and then we’ll learn how the temple as a whole functions as a symbol of Ancient Egyptian mythology and spiritual beliefs.

If you enjoy the podcast and want to help support it, please consider leaving your comments on iTunes and YouTube. You can also give your feedback at ancientartpodcast.org. Just click on the Feedback link at the top of the page. And I appreciate your comments, suggestions, and questions at info@ancientartpodcast.org. Thanks for listening and see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2010 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[1] Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000, p154.