The following blog post features additional content not included in the video podcast. Enjoy!

Hello fellow explorers! Welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m your intrepid host, Lucas Livingston. If you’re wondering why we jumped from episode 62 to 64, it’s because the past two episodes were released exclusively as illustrated blog posts at ancientartpodcast.org. If you haven’t yet done so, I hope you’ll check out episodes 62 and 63 — parts two and three in my three-parter on dogs in antiquity. The trilogy explores the hairless dogs of ancient Mexico and Peru, dogs in ancient China, and our canine companions in Greco-Roman antiquity.

Here’s a cool cat strutting his stuff down easy street. With his arms a-swinging and legs a-striding, this little guy in the Art Institute of Chicago is on the go. That glorious green skin might have you thinking of the purity of Chinese jade, but this dude’s made of copper. One solid cast piece. He’s also one of the oldest pieces in the Art Institute, being around 5,000 years old. He’s dated to about 3,100 BC from the Proto-Elamite culture. (The what!?) Yeah, I know. Proto-Elamite is one of the earlier cultures around that hotbed of civilization we call the ancient Near East. Frankly with the litany of different cultures and civilizations from Mesopotamia and its environs, if you don’t know your Assyria from your Ubaid, you’re in fairly good company.

Here’s a cool cat strutting his stuff down easy street. With his arms a-swinging and legs a-striding, this little guy in the Art Institute of Chicago is on the go. That glorious green skin might have you thinking of the purity of Chinese jade, but this dude’s made of copper. One solid cast piece. He’s also one of the oldest pieces in the Art Institute, being around 5,000 years old. He’s dated to about 3,100 BC from the Proto-Elamite culture. (The what!?) Yeah, I know. Proto-Elamite is one of the earlier cultures around that hotbed of civilization we call the ancient Near East. Frankly with the litany of different cultures and civilizations from Mesopotamia and its environs, if you don’t know your Assyria from your Ubaid, you’re in fairly good company.

To seriously geek out for a minute though, the Proto-Elamite period is recognized for its distinct hybridization of early Mesopotamian and western Iranian motifs, as the people of the Elamite region became culturally and linguistically independent from Sumer. Animals engaged in human ritual activities held significant meaning. [1] And the composite man-beast hero descending from the mountain already had a long history stretching back some 2,000 years earlier. [2]

To seriously geek out for a minute though, the Proto-Elamite period is recognized for its distinct hybridization of early Mesopotamian and western Iranian motifs, as the people of the Elamite region became culturally and linguistically independent from Sumer. Animals engaged in human ritual activities held significant meaning. [1] And the composite man-beast hero descending from the mountain already had a long history stretching back some 2,000 years earlier. [2]

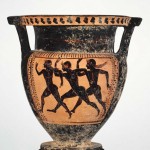

At first glance, his posture might remind us of the pharaohs, gods, and standing figures of Ancient Egypt, but it doesn’t take long to see how very different he is from the Egyptian type. The left leg is forward, sure, but unlike the Egyptian form, the right leg is also at an angle forming a realistic stride. His knees are also bent, like we do when we walk. His arms are also pumping as in mid stride. Note while the left leg is forward, his right arm is extended, realistically capturing a typical human gait. This reminds me of ancient Greek vessels with painted images of athletes running races. We can often identify which footrace is depicted based on the positions of the runners. Arms are tucked in closely for the long distance dolichos, whereas it’s an all out sprint for the short stadion. Our guy here seems somewhere in between with arms tucked in and both feet planted on the ground. It seems he might be out for a power walk.

At first glance, his posture might remind us of the pharaohs, gods, and standing figures of Ancient Egypt, but it doesn’t take long to see how very different he is from the Egyptian type. The left leg is forward, sure, but unlike the Egyptian form, the right leg is also at an angle forming a realistic stride. His knees are also bent, like we do when we walk. His arms are also pumping as in mid stride. Note while the left leg is forward, his right arm is extended, realistically capturing a typical human gait. This reminds me of ancient Greek vessels with painted images of athletes running races. We can often identify which footrace is depicted based on the positions of the runners. Arms are tucked in closely for the long distance dolichos, whereas it’s an all out sprint for the short stadion. Our guy here seems somewhere in between with arms tucked in and both feet planted on the ground. It seems he might be out for a power walk.

His fists are a bit stylized, clenched with thumbs resting on top. There’s something emblematic about that gesture — assertive yet not quite poised to strike. Do we have a subconscious psychological reaction of submission, deference, or assent to that gesture? As political commentators like to point, it’s a gesture often made at the podium by American presidents. Do speech coaches know something we don’t? It’s also a gesture paralleled in royal iconography of Sumer, the emerging Mesopotamian superpower contemporary to our figurine, along with his thick-banded cap, wide belt, and artificial-looking beard. [3]

How about those horns, though!? The great curling horns of the ibex crowning his head evoke the mountainous spirit of the western highlands of Elam. His cap’s pointy ears further accentuate his beastly side as does the vulture wrapped about his torso like some sort of superhero’s cape. In fact, when I was recently looking at this figure in the gallery, one of the museum security officers asked me, “So, was this like an action figure?” Precisely! Maybe not a kid’s toy with kung fu action grip, but “action figure” certainly captures the heroic, mythological, and spiritual power embodied in a mere 7 inch figure.  But wait, there’s more. Act now and you’ll get two for the price of one! That’s right, there are two ancient horned action figures! One belongs to a private collection and has been on loan to the Art Institute of Chicago; the other is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

But wait, there’s more. Act now and you’ll get two for the price of one! That’s right, there are two ancient horned action figures! One belongs to a private collection and has been on loan to the Art Institute of Chicago; the other is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

So, who is he? Is he a god-king shrouded in animalistic associations? Is he a mythological hero; some sort of Proto-Elamite Hercules? We remember that Hercules wrapped himself in the pelt of a lion, while our hero here sports the raptor cloak (another carnivorous predator). Both figures embody a sort of “wild man,” an ancient figural type capturing our struggle to grasp our nature as a civilized creature living in a world of beasts, and ultimately derived from the wilds. It’s worth pointing out, though, that the distance in time between our friend here and the earliest mentions of Hercules is about the same as the distance between the earliest mentions of Hercules and us today. Translation, about 2,500 years.  A little closer to home, though, our action hero might remind us of Enkidu from the ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, the wild man and eventual sidekick to the eponymous hero, Gilgamesh. While Enkidu first emerges from the wilds, raised by animals and ignorant of human civilization, he gradually tames throughout the story. We might draw a parallel here to the Proto-Elamite culture living between two worlds: the animistic, shamanistic, tribal society of the highlands and the urbanized, theistic, bureaucratic monarchy of Sumer.

A little closer to home, though, our action hero might remind us of Enkidu from the ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, the wild man and eventual sidekick to the eponymous hero, Gilgamesh. While Enkidu first emerges from the wilds, raised by animals and ignorant of human civilization, he gradually tames throughout the story. We might draw a parallel here to the Proto-Elamite culture living between two worlds: the animistic, shamanistic, tribal society of the highlands and the urbanized, theistic, bureaucratic monarchy of Sumer.

The two versions of our hero — the Metropolitan’s and the one in the Art Institute — are just different enough to make us wonder if they came from separate molds or if the variations are simply from aeons of separate wear and tear. The one in the Art Institute still has some bits of shell or stone forming the white of the eyes. The pupils are lost, but were made of some other sort of separate contrasting material.

We’ve seen here through various associations and affiliations the many different interpretations that the striding figure may evoke. The Metropolitan calls their figure a striding horned demon, but I comfort myself in speculating that they’re using demon in the original Greek context of a divine entity, nature spirit, or deified hero. [4]

But I’ll tell you one thing in my own personal opinion.

We have before us an ethically nebulous minion.

With those curly elf boots and big bushy beard,

Horns soaring atop his cute pointy ears,

When I say this indeed you’ll surely feign sick,

But he may be a prototype for jolly Saint Nick!What? Santa, you say? Well, you’re clearly insane.

But I’m speaking of course of the less popular vein,

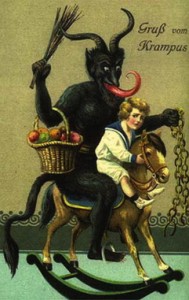

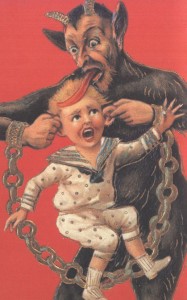

Of the horned wicked Santa of unfashionable lore,

Like the Nordic Julbocken, surely related to Thor.

Knecht Ruprecht and Perchta, Belsnickel, Zwarte Piet

Are but some of the sidekicks Santa brings on his beat.But the one most inspired for a good Christmas fright

Is none other than Krampus … an Austrian Elamite?

Two years ago as I previously warned you,

There’s an honored tradition that the Church cannot undo.

Search in my archives for the great Christmas Devil.

Since the dawn of the ages in the Wild Man we revel.

For a topic befitting the learned on campus

Click on ancientartpodcast.org/krampus

Thanks so much for tuning in to the Ancient Art Podcast and for all the support over the years. If you dig this shot of educational espresso, please consider leaving a little something in the tip jar. Just head on over to ancientartpodcast.org and click on the juicy “Donate” button. Any amount helps me pay for bandwidth and keep’n it real! And if you can’t spare a buck or two, give me a fat five star rating and comment on iTunes, subscribe, thumbs up, and share my YouTube channel, like and share the podcast on Facebook at facebook.com/ancientartpodcast, and follow me on Twitter @lucaslivingston. If you wanna drop me a line, go to ancientartpodcast.org/feedback or email me at info@ancientartpodcast.org.

©2014 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[1] Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Ed. Joan Aruz with Ronald Wallenfels. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003, p. 43.

[2] ibid. p. 46.

[3] “Recent Acquisitions: A Selection: 2007–2008.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 66, no. 2 (Fall 2008), p. 6.

[4] For reference to the Striding Figure as a “horned demon,” see:

“Recent Acquisitions,” p. 6 & Art of the First Cities, p. 46

For the ancient Greek meaning of “demon,” see the entry in the Perseus Project’s Greek Word Study Tool.

———————————————————

Visit my Flickr gallery for this episode for detailed image credit.

———————————————————

Additional credits:

Maria Girbiat

Anon – Medieval Dance Tunes

Performed by Paul Arden-Taylor

Released in the public domain

musopen.org

Zapac

Put your hands up (funky mix)

Licensed under Creative Commons

ccmixter.org

Rutger Muller

Haunting Music 1

Released in the public domain

freesound.org

Just found your great analysis of this figure. I was doing a google image search to try to find a similar image to a figure I own in the form of an ancient roman vessel handle. It’s also made of bronze. He has similar ibex horns and small upturned ibex ears up top, but his face is part man, part goat, with drooping goat ears and a long pointy beard. Can I send you some photos for your opinion on who he might represent?