Hey people. Welcome back. I’m excited to announce that we’re undergoing a little re-branding here. We’re dropping the SCARABsolutions and now it’s the Ancient Art Podcast. The website scarabsolutions.com will continue to work, but now you can also visit us at ancientartpodcast.org and you can reach me with your comments, questions, and suggestions at info@ancientartpodcast.org.

Last time in episode 15 we set the stage for the origin of free-standing, monumental sculpture in Ancient Greece. We revisited the Greek Orientalizing Period with its Near Eastern influences in vase painting technique and subject matter, and we discussed the strong Greek presence in Egypt during the Egyptian Saite Dynasty of 664 to 525 BC. In this new cultural melting pot of Egypt, archaeological evidence points to an Egyptian influence on the sacred art and ritual practice of Ancient Greece. Greeks are visiting Egyptian temples, gazing in awe at the centuries-old monumental sacred structures while giving gifts to Egyptian gods of bronze Egyptian votive statuary with inscribed with Greek prayers. And Greek votive statuary starts to bear a resemblance to common Egyptian types like this figurine of a seated woman nursing a child, which may have been influenced by the popular figure type of Isis nursing the child Horus.

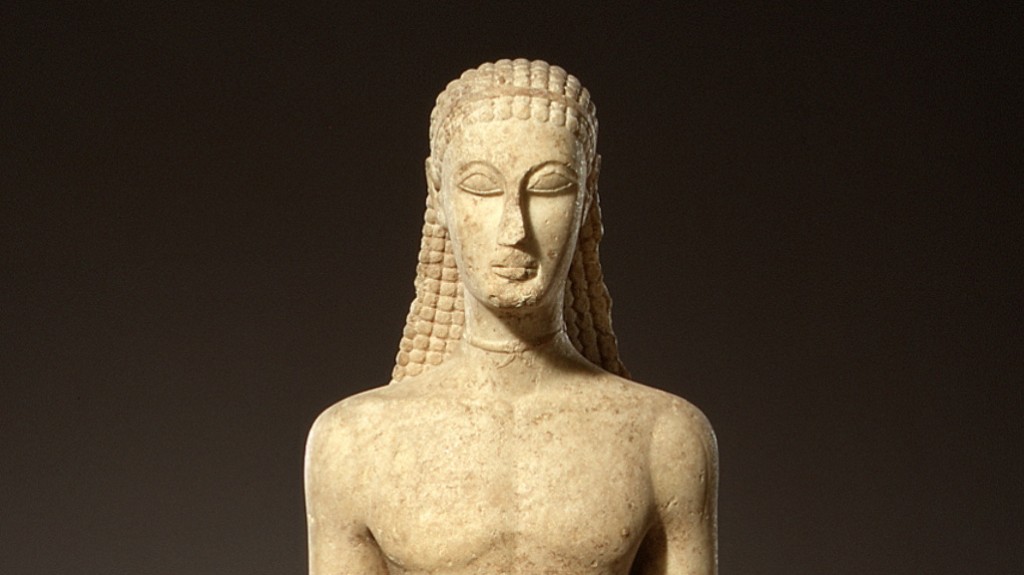

Diminutive votive figurines are one thing, but the big development that we’re interested in here is the advent of monumental, free-standing Greek sculpture some time in the 7th century BC. That’s right … “some time.” We don’t know exactly when the Greeks began creating sculpture, but we do know that, after the collapse of the Bronze Age Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations, there was a long period of time when the most elaborate figural works produced by the Greeks were small figurines and relief carvings of stone, terracotta, and bronze. The advent of monumental sculpture in the 7th century was a huge development, and by “monumental” I mean big and made of something durable, like stone or metal. And what’s really remarkable is the style of the earliest known Greek sculptures. Here we have one of the earliest and most intact Greek statues of the kouros type. “Kouros” is simply the Greek word for “boy.” This kouros, carved from a single block of marble, is dated to about 590-580 BC. It’s at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and it’s unofficial name in the scholarly arena is … wait for it … the Metropolitan Kouros. Sheer genius. He’s large as life, about 6′ 4″ or 1.946 m tall—I guess larger than life for most Ancient Greeks—but look at the pose. All early kouroi appear in a nearly identical pose. Broad straight shoulders, arms straight down at his sides, strong frontal stare, tall vertical posture, and his left leg stepping forward a bit. Remind you of anything? How about the figure of Ra-Horakhty that we looked at last time in episode 14? The Greek kouros is borrowed directly and heavily from the popular Egyptian standing male, the statue type that has a widespread prominent presence throughout Egypt, from miniature religious votives to colossal tomb and temple sentinels. The Greek mercenaries, merchants, artisans, and travelers to Egypt, which we talked about last time, had regular opportunity to be in contact with the long tradition of Egyptian statuary, which no doubt encouraged similar artistic development back home.

As I said earlier, he’s carved out of a single block of stone, and he retains a sort of blocky shape. Following the Egyptian technique for executing a stone carving, the sculptor took a large rectangular block of stone, drew the figure’s front, back, left, and right sides onto their respective sides of the block, and went to work, gradually removing stone from all four sides, working his way inward until the sides met, producing a free-standing figure in the round. It’s an efficient technique, but typical of early Greek kouroi, each side retains a sort of flattened planar effect. He’s somewhat in between being completely rounded and being a four-sided figure.

Another thing that the kouros and Egyptian statuary had in common, but it’s often overlooked on both accounts, is color. That’s right, as with so many examples of ancient art, which now appear in the crisp, pristine, unadulterated purity of a more noble and stoic age, the kouros was originally highly painted in a variety of colors meant to mimic real life—flesh tones, dark hair, brown eyes, full dark eyebrows, a cute little red necktie like the good boy scout he is. A lot of work has been done to reconstruct the original color on ancient statuary and architecture, but that’s a topic for a later episode. If you want to get a head start, though, check out a couple websites: The Color of Life: Polychromy in Sculpture from Antiquity to the Present, an exhibition that was at the Getty Villa in California from March to June of 2008, and also Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity that was at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum a little earlier in the year. Just Google them or click on the links in the Additional Resources section at ancientartpodcast.org.

Putting aside the broad similarities between Egyptian statuary and Archaic Greek kouroi, one subtle similarity I like to note is the quirky Mona Lisa smile, also called the “Archaic smile.” Because why would you want to spend all this time and money on a frowning statue? But you’ll notice a few differences between the Egyptian statue type and the Greek kouros. For starters, there are some formal differences. In addition to replacing the Egyptian wig with those lovely, cascading, curly Greek locks, the kouros figure is clearly in the nude. For the most part, Egyptian statuary of this standing type were somewhat clothed. At least a kilt, please! Sure, there are some nude examples from Egypt, but those are rare and generally not plastered all over the place. So, why is the kouros represented in the nude? Here’s another prime example of the Greeks adopting a foreign concept and immediately adapting it to suit their own needs. The nudity of the kouros is directly related to its function. The Greeks didn’t have the ancient tradition of mighty Pharaoh to venerate in all of his three-story glory, but two other functions of statuary from Egypt could easily be adapted to Greece—that is, as monumental temple dedications and as grave markers … tombstones. Greece already had a long tradition of honoring the dead with elaborate ceramic memorials. Many of the colossal vessels of the Geometric Period were crafted to be set up as grave markers in the Dipylon Cemetery of the Athenian ceramics district, the Kerameikos. These monumental vessels weren’t functional on a practical level. They even had holes drilled into the bottom to prevent collecting water. Wealthy Athenian families during the 7th century BC erected lavish displays of conspicuous wealth in honor of their deceased family members, so much so that the famous Athenian statesman Solon actually passed legislation restricting the expense on private funerals. So, but with the advent of sculpture in Greece, it’s not unreasonable to understand a fashionable movement towards decorating graves with this trendy new art form.

As grave markers, the kouros type generally decorated the graves of fallen youths. Young men lost before their prime. Maybe heroic youths fallen on the battlefield, or so the symbolism suggests. The nude form of the kouros casts the fallen youth in the light of the heroic warrior. Heroic warriors like Achilles, Odysseus, and Hercules are generally depicted fighting in the nude. Yes, of course, Greek warriors of history fought heavily armored, complete with breastplate, greaves, helmet, and shield, but in myth the hero would fight in the nude. So here the individual commemorated by the kouros is elevated to heroic status. But there’s a second idea at work here. The nude form of the kouros might also remind us of a youth participating in athletics, which the Greeks did indeed do in the nude. So, here we have a fallen youth commemorated as the proud athlete participating in perhaps what his family believes he ought to have been doing back home in the safety of the Athenian gymnasium, rather than marching to far off lands only to die on the battlefield. It’s an interesting tug in two directions, a dual interpretation, which … hey, maybe I’m just making this up, but the hero and the athlete are two of the most popular subjects for the human male form throughout the history of Greek sculpture.

If you want to read a meticulous examination of the Metropolitan Kouros, check out the authoritative article by Gisela M. A. Richter and Irma A. Richter “The Archaic ‘Apollo’ in the Metropolitan Museum” published in the Metropolitan Museum Studies, volume 5, number 1 from August 1934. Like fine scotch, some articles keep well with age. Notice “Apollo” in that article title. That’s because back in the early part of the 20th century, kouroi were generally referred to as “Apollo figures,” a term which has since been dismissed.

So, with the kouros, Ancient Greece begins its spectacular journey exploring the possibilities of sculpture, opening the floodgates for a revolution that would define the artistic heritage of Western Civilization. And that, friends, is a story for another day.

©2008 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org