Hey people. Welcome back. I’m excited to announce that we’re undergoing a little re-branding here. We’re dropping the SCARABsolutions and now it’s the Ancient Art Podcast. The website scarabsolutions.com will continue to work, but now you can also visit us at ancientartpodcast.org and you can reach me with your comments, questions, and suggestions at info@ancientartpodcast.org.

Last time in episode 15 we set the stage for the origin of free-standing, monumental sculpture in Ancient Greece. We revisited the Greek Orientalizing Period with its Near Eastern influences in vase painting technique and subject matter, and we discussed the strong Greek presence in Egypt during the Egyptian Saite Dynasty of 664 to 525 BC. In this new cultural melting pot of Egypt, archaeological evidence points to an Egyptian influence on the sacred art and ritual practice of Ancient Greece. Greeks are visiting Egyptian temples, gazing in awe at the centuries-old monumental sacred structures while giving gifts to Egyptian gods of bronze Egyptian votive statuary with inscribed with Greek prayers. And Greek votive statuary starts to bear a resemblance to common Egyptian types like this figurine of a seated woman nursing a child, which may have been influenced by the popular figure type of Isis nursing the child Horus.

Diminutive votive figurines are one thing, but the big development that we’re interested in here is the advent of monumental, free-standing Greek sculpture some time in the 7th century BC. That’s right … “some time.” We don’t know exactly when the Greeks began creating sculpture, but we do know that, after the collapse of the Bronze Age Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations, there was a long period of time when the most elaborate figural works produced by the Greeks were small figurines and relief carvings of stone, terracotta, and bronze. The advent of monumental sculpture in the 7th century was a huge development, and by “monumental” I mean big and made of something durable, like stone or metal. And what’s really remarkable is the style of the earliest known Greek sculptures. Here we have one of the earliest and most intact Greek statues of the kouros type. “Kouros” is simply the Greek word for “boy.” This kouros, carved from a single block of marble, is dated to about 590-580 BC. It’s at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and it’s unofficial name in the scholarly arena is … wait for it … the Metropolitan Kouros. Sheer genius. He’s large as life, about 6′ 4″ or 1.946 m tall—I guess larger than life for most Ancient Greeks—but look at the pose. All early kouroi appear in a nearly identical pose. Broad straight shoulders, arms straight down at his sides, strong frontal stare, tall vertical posture, and his left leg stepping forward a bit. Remind you of anything? How about the figure of Ra-Horakhty that we looked at last time in episode 14? The Greek kouros is borrowed directly and heavily from the popular Egyptian standing male, the statue type that has a widespread prominent presence throughout Egypt, from miniature religious votives to colossal tomb and temple sentinels. The Greek mercenaries, merchants, artisans, and travelers to Egypt, which we talked about last time, had regular opportunity to be in contact with the long tradition of Egyptian statuary, which no doubt encouraged similar artistic development back home.

As I said earlier, he’s carved out of a single block of stone, and he retains a sort of blocky shape. Following the Egyptian technique for executing a stone carving, the sculptor took a large rectangular block of stone, drew the figure’s front, back, left, and right sides onto their respective sides of the block, and went to work, gradually removing stone from all four sides, working his way inward until the sides met, producing a free-standing figure in the round. It’s an efficient technique, but typical of early Greek kouroi, each side retains a sort of flattened planar effect. He’s somewhat in between being completely rounded and being a four-sided figure.

Another thing that the kouros and Egyptian statuary had in common, but it’s often overlooked on both accounts, is color. That’s right, as with so many examples of ancient art, which now appear in the crisp, pristine, unadulterated purity of a more noble and stoic age, the kouros was originally highly painted in a variety of colors meant to mimic real life—flesh tones, dark hair, brown eyes, full dark eyebrows, a cute little red necktie like the good boy scout he is. A lot of work has been done to reconstruct the original color on ancient statuary and architecture, but that’s a topic for a later episode. If you want to get a head start, though, check out a couple websites: The Color of Life: Polychromy in Sculpture from Antiquity to the Present, an exhibition that was at the Getty Villa in California from March to June of 2008, and also Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity that was at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum a little earlier in the year. Just Google them or click on the links in the Additional Resources section at ancientartpodcast.org.

Putting aside the broad similarities between Egyptian statuary and Archaic Greek kouroi, one subtle similarity I like to note is the quirky Mona Lisa smile, also called the “Archaic smile.” Because why would you want to spend all this time and money on a frowning statue? But you’ll notice a few differences between the Egyptian statue type and the Greek kouros. For starters, there are some formal differences. In addition to replacing the Egyptian wig with those lovely, cascading, curly Greek locks, the kouros figure is clearly in the nude. For the most part, Egyptian statuary of this standing type were somewhat clothed. At least a kilt, please! Sure, there are some nude examples from Egypt, but those are rare and generally not plastered all over the place. So, why is the kouros represented in the nude? Here’s another prime example of the Greeks adopting a foreign concept and immediately adapting it to suit their own needs. The nudity of the kouros is directly related to its function. The Greeks didn’t have the ancient tradition of mighty Pharaoh to venerate in all of his three-story glory, but two other functions of statuary from Egypt could easily be adapted to Greece—that is, as monumental temple dedications and as grave markers … tombstones. Greece already had a long tradition of honoring the dead with elaborate ceramic memorials. Many of the colossal vessels of the Geometric Period were crafted to be set up as grave markers in the Dipylon Cemetery of the Athenian ceramics district, the Kerameikos. These monumental vessels weren’t functional on a practical level. They even had holes drilled into the bottom to prevent collecting water. Wealthy Athenian families during the 7th century BC erected lavish displays of conspicuous wealth in honor of their deceased family members, so much so that the famous Athenian statesman Solon actually passed legislation restricting the expense on private funerals. So, but with the advent of sculpture in Greece, it’s not unreasonable to understand a fashionable movement towards decorating graves with this trendy new art form.

As grave markers, the kouros type generally decorated the graves of fallen youths. Young men lost before their prime. Maybe heroic youths fallen on the battlefield, or so the symbolism suggests. The nude form of the kouros casts the fallen youth in the light of the heroic warrior. Heroic warriors like Achilles, Odysseus, and Hercules are generally depicted fighting in the nude. Yes, of course, Greek warriors of history fought heavily armored, complete with breastplate, greaves, helmet, and shield, but in myth the hero would fight in the nude. So here the individual commemorated by the kouros is elevated to heroic status. But there’s a second idea at work here. The nude form of the kouros might also remind us of a youth participating in athletics, which the Greeks did indeed do in the nude. So, here we have a fallen youth commemorated as the proud athlete participating in perhaps what his family believes he ought to have been doing back home in the safety of the Athenian gymnasium, rather than marching to far off lands only to die on the battlefield. It’s an interesting tug in two directions, a dual interpretation, which … hey, maybe I’m just making this up, but the hero and the athlete are two of the most popular subjects for the human male form throughout the history of Greek sculpture.

If you want to read a meticulous examination of the Metropolitan Kouros, check out the authoritative article by Gisela M. A. Richter and Irma A. Richter “The Archaic ‘Apollo’ in the Metropolitan Museum” published in the Metropolitan Museum Studies, volume 5, number 1 from August 1934. Like fine scotch, some articles keep well with age. Notice “Apollo” in that article title. That’s because back in the early part of the 20th century, kouroi were generally referred to as “Apollo figures,” a term which has since been dismissed.

So, with the kouros, Ancient Greece begins its spectacular journey exploring the possibilities of sculpture, opening the floodgates for a revolution that would define the artistic heritage of Western Civilization. And that, friends, is a story for another day.

©2008 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

Hello and welcome back to the SCARABsolutions Ancient Art Podcast. In our last episode on the Art Institute of Chicago’s Corinthian pyxis, we saw how the early Archaic Greeks of the Orientalizing Period incorporate stylistic elements and ideas from their Near Eastern neighbors and also from their own Bronze Age ancestors. We looked at the emergence of monumental Greek temple architecture with its unprecedented massively impressive pedimental sculpture. And ultimately we came to understand how the Greeks paid homage to their Mycenaean Bronze Age ancestors by employing scenes of ferocious beasts and fiendish monsters on these early temple pediments. They did this as a means of confronting the viewer, engaging with them and conditioning their psyche for approaching the divine, just as the Mycenaeans did half a millennium earlier at the entrance to the great city of Mycenae. And on a far more diminutive, personal scale, we see this same confrontational conditioning effect employed on the funerary vessels of this early Archaic period in Ancient Greece as a sort of memento mori, a reminder of our ultimate fate.

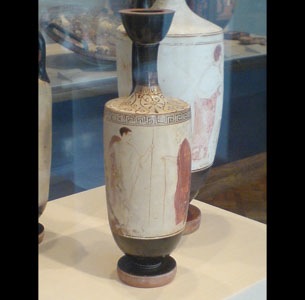

In this episode, I want us to take a look at a significantly later example of Greek pottery and vase painting, also at the Art Institute of Chicago. This is an Attic white-ground ware lekythos from around 450-440 BC attributed to the Achilles Painter. OK … what does all that mean? Well, you’ll often come across the term “Attic” on gallery labels. That’s got nothing to do with where you keep your Christmas lights. Attic means it’s from Attica, which is the region of Greece that surrounds Athens. Aha! … Moving along now. “White-ground ware!?” See, you got yer black figure vase painting and yer red figure vase painting … and then you got your white-ground ware, because the figures are on a white background and “ware” is just the fancy word for ceramics … you know, like dinner ware. And finally a lekythos is a specific type of Ancient Greek pottery vessel usually in a tall slender vase-like shape with a tight spout and a handle, but you come across small more squat versions too. The lekythos was specifically use as a decanter for oil, mostly olive oil for Ancient Greek athletes. Now, the Greeks lived in a time before the invention of soap. Filthy buggers!? Not really. See, olive oil is an exceptionally good cleaning agent (not to mention a common ingredient in some exotic old-fashioned soaps). After a long day of rolling around with your classmates naked in the sand at the gymnasium, Greek athletes would rub olive oil on their lean, tight flesh. They’d then take a small curved metal tool called a strigil and scrape it along their skin, removing the oil and all the grime, sweat, and guck. Don’t believe me? Next time you take off a day-old BAND-AID® and it leaves behind that yucky glue residue, rub a little olive oil over it for a few seconds and presto! — ancient goo-begone. [This does not necessarily constitute an endorsement, neither expressed nor implied, of the aforementioned products BAND-AID® brand bandages and Goo Begone or any similar or related products on the part of the author or his affiliates; use at your own risk; do not attempt this at home; yadda yadda, etc etc.]

Before we dive headlong into the subject matter of this lekythos, I want to explain why the painted surface is not nearly in as good condition as most of the black and red figure vases you’ll spot at the Art Institute. You see, in the white-ground technique, the white background was painted onto the surface of the vessel after it had been fired and then the figures were painted on top of that. All the decoration of black or red figure vases was applied before the firing process as slip (not actually paint) and then fired, so baking the decoration onto the surface so it ain’t goin’ nowhere. Paint applied to the surface after firing, however, isn’t as durable and it’s prone to flaking over the eons.

The scene decorating this lekythos depicts a gray-haired elderly man with a long red cloak leaning on a cane. He looks forward into the eyes of a youthful mostly-nude male figure with a shield strapped to his back and holding a spear. The fact that the youth is nude indicates his function as a warrior. (And the shield and spear kinda help us draw that conclusion too.) Warriors in Ancient Greece, of course, didn’t march out onto the battlefield in the nude, not unless they had a few too many at the feast the night before. No, they were fully armored with a sturdy breastplate, greaves on the legs, and a helmet. Excavations in the latter part of the 20th century at Midea near Mycenae actually unearthed a magnificent Bronze Age Mycenaean cuirass or a breastplate from the 15th century BC, the time of the great heroic warriors whose legacy inspired the later epics, now in the Archaeological Museum of Nauplion in Greece. Check out the website — scarabsolutions.com — for a link to an image and description of the armor and the excavations at Midea. There’s also an interesting article in the March/April 2007 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review called “Historic Homer: Did It Happen?” which talks about this breastplate and other Mycenaean-period historical accuracies in the Iliad and Odyssey.

Despite the obvious use of armor, however, Greek artists imagined their mythological heroes were in fact nude. Throughout Ancient Greek vase painting we encounter the nude warrior, be it Hercules, Achilles, Hector, or any other heroic mythic warrior. Many a Greek male was fond of casting himself in the light of the mythic warrior, particularly upon death through the use of the nude male kouros statue as a headstone. The kouros is the earliest form of freestanding monumental Greek sculpture in the round, which finds its origin around the time of the Orientalizing Period, which we covered last time when looked at the pyxis. Perhaps a similar sort of desired effect is being attempted here — to cast the deceased in the light of the heroic warriors of yore. Remember, just about all the Ancient Greek vases you encounter in museum collections were actually grave goods. One might be inclined to interpret this scene depicted here as a father figure bidding farewell to the youth; their final goodbye before the youth marches off to battle. Perhaps the last time they will ever see each other … alive, at least. Neither figure has an expression of overwhelming emotion. They both bear a sober countenance, not betraying their torn spirits within.

Think about the difference in the way I’m describing the subject matter of this vase painting compared to the Corinthian pyxis from a century earlier. We’re trying to get inside the heads of the figures represented on the lekythos; we’re looking at a scene from some dreamt-up story. There’s definitely some sort of context here, in contrast to the decoration on the pyxis, where the creatures are outside of any context, any narrative or story. This is a big change taking place in late 6th, early 5th century Greek vase painting – a movement away from representations of ferocious confrontational beasts towards narrative scenes. Sure, representations of the Homeric epics go way back, but the narrative becomes firmly entrenched only in the mid to late Archaic Period, pushing aside the decorative flower patterns and the prominence of confrontational beasts common to the Orientalizing Period.

Beyond the heroic mythologized warrior, the nude in Ancient Greece also fires another neuron. I’m talking about the Greek athlete. Unlike the imaginary mythical nude hero, Greek athletes did in fact compete in the nude. Easy there tiger. The representation of this youth in the nude might draw us in two different directions. While all geared up, the youth is clearly preparing to head off for battle, but this solemn goodbye reminds us of the other activity of Greek youths — athletics, which perhaps the old man wishes the youth would sooner be doing before heading off to battle. And don’t forget the vessel on which this scene is depicted — a lekythos — a jar for an athlete’s oil bath. So what’s going on here? Why is the artist conjuring up a scene that might tug us in two directions? Well, just as with the Corinthian pyxis that we looked at before, this lekythos is also a funerary vessel, a grave good. So, to take our train of imaginative thought one step further, perhaps we have a scene here reflecting an actual occurrence or some imagined, mythologized, heroicized occurrence of a youth slain in battle, the loss of innocence, no more will he enjoy sport at the gymnasium with his fellow companions. So, he’s buried with a lekythos to recapture the activities of youth and he’s portrayed here as a heroic warrior worthy of all honor. Just as with the pyxis, here too we have a memento mori.

We see a big change taking place in the Archaic period as Athens emerges as the new cultural superpower, soon eclipsing Corinth. Perhaps the most significant stamp that Athenians place on the Greek world is their interest in the human condition, in morality, justice, pride, and suffering. And this shows up in their vase painting not so much in the stories that they tell, but more so in the way that they tell their stories. The artist could have chose to memorialize the deceased as a fallen warrior among other glorious dead or in the moment of a heroic death on the battle field. Or he could have represented some other mythical hero like Hercules, Achilles, or Perseus, casting the deceased in a brighter light. Instead we see a different sort of narrative aesthetic evolving in Attic vase painting. Well, by this Late Classical period it’s pretty much well evolved. Instead of showing the height of physical action, instead we’re presented with a subdued anticlimactic moment of pause, the quiet before the storm. It’s up to the mind of the viewer, up to us, to complete the narrative in our minds. Granted, this narrative technique relies on a sort of familiarity with the story. In this case, we may not necessarily be familiar with the story, but different clues like the nude form of the youth, his armament, and his classical contaposto (that’s the stance he’s taking, like a statue of some hero) — these clues lead us to the conclusion that he’s a warrior and the old man seems to be engaging with him. The rest is our own speculation, but it’s an educated and informed speculation.

We encounter a lot of similar examples in Archaic and Classical Attic vase painting where a moment just before the height of the climax is represented, rather that showing all the gory details, and the artist relies on the viewer’s familiarity with the narrative to connect the dots and lead up to the climax in his or her mind. Here’s a fairly early and exemplary illustration, The Suicide of Ajax, an Attic black-figure amphora from around 540 BC by the very well known artist Exekias, now in the Château-Musée de Boulogne-sur-Mer (er … pardon my French). Ajax fought alongside Achilles in the Trojan War. In later myths and tragedies, he’s often elevated practically to the same status as Achilles. Alas, he’s probably most familiar to our contemporary audience as the big goober with the war hammer in the 2004 Hollywood production Troy, where Achilles is played by Brad Pitt. The Iliad just tells a fraction of the story of the siege of Troy. A lot happens between the Iliad and the Odyssey, where the latter recounts Odysseus’s journey back home from the 10 year-long siege. Apparently there were also other epics that told the stories of other warriors involved in the Trojan War beyond Achilles and Odysseus, sadly now lost – well … till somebody discovers a Greco-Roman mummy stuffed with papyrus fragments of some lost epic. … It’s not impossible.

But somewhere between the events of the Iliad and Odyssey, the unthinkable happens – Achilles is killed by Orlando Bloom … I mean, Paris. The armament of Achilles is to be rewarded to the most feared Greek soldier. It comes down to Odysseus and Ajax. They get into a big debate and the arms are finally awarded to Odysseus. There’re different accounts of what happens next, but one popular version says Ajax is completely distraught and goes into a mad rage, killing his Greek comrades left and right … or so he thought. Athena intervened and disguised the flocks as his fellow Greeks, so Ajax ended up only slaying the flocks. Completely embarrassed and distraught a second time for the harm he could have done, Ajax takes the sword of Hector (awarded to him after a stalemate battle against Hector), wanders off from the camp, and kills himself by burying the sword tip-up in the sand and impaling himself on it. So, here we see Ajax planting the sword, neatly packing down the earth around it. His shield leans lazily at the edge of the frame, his helmet and spears carefully placed atop. Incidentally, the spear was his weapon of choice, not the war hammer. And now we know what’s coming next. … Bleeehh! See, Exekias is relying on our familiarity with the story to bring us to the height the climax and all the gory bits without having to show the gory bits. It’s more engaging, less off-putting, and invites us to consider the Ajax’s state of mind. To ponder his pathos, the powerful Greek term for suffering and the human condition. And as if that’s not enough, Exekias also sneaks in a foreboding omen. Decorating the shield of Ajax is the fiendish Gorgon Medusa with snakes for hair, said to have been so hideously ugly that her gaze would turn you to stone. And above that is a glaring feline, similar devices to the ones we saw on the Corinthian pyxis. While it’s perfectly legitimate to have these devices decorating your shield (wouldn’t be a pretty sight to have that racing towards you on the battlefield), they also function in the context of the painting as ill omens of the impending tragic conclusion.

My goodness … how about that.

Thanks for listening. Don’t forget to hop on over to the website scarabsoltions.com for better quality images, links to external resources, and the extensive bibliography on Ancient art. I’m also adding transcripts for each episode, in case you’d prefer to read rather than listen to the podcast. That’ll also make it a lot easier if you want to revisit something you heard on the podcast, but can’t remember exactly where it was mentioned. Simply enter some keywords in the search box at scarabsolutions.com. And in case you haven’t noticed, you can leave your feedback for each individual episode at the website, if you have something nice to say or a particular axe to grind. You can also email me at scarabsolutions@mac.com. And while you’re at it, if you like the podcast, I invite you to go on over to iTunes and post a review. It’s gettin’ a little lonely out here. Take care and see ya soon on the SCARABsolutions Ancient Art Podcast.

©2007 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

Welcome back to the SCARABsolutions Ancient Art Podcast. This episode is coming out a little later than I had wanted on account of a cold that I’ve been getting over. But I’m pretty much decongested now and more or less back to normal.

In this episode, I want us to take a look at a cute little pyxis from Corinth. A pyxis is a specific type of Greek vessel used to store cosmetics, jewelry, or other trinkets. They come in a variety of different shapes—squat basket-like, cylindrical jars, box-like, and spherical, as we have here, along with a separate lid and handles. This pyxis at the Art Institute of Chicago is dated to about 580-570 BC, towards the end of the Greek Orientalizing Period, late 8th to mid 6th centuries BC. The Orientalizing Period is a time when the Greeks renew contact and trade with the different civilizations of the Mediterranean and the Ancient Near East after a long period of isolation during the Greek Dark Age and Geometric Period. This is a fascinating time of rediscovery, invention, and assimilation.

Albeit not the most politically correct term, the “Orientalizing Period” has nonetheless stuck. The term refers to the tremendous cultural and artistic impact that the renewed contact with Ancient Near Eastern cultures had on the blossoming civilization of Greece. One particularly successful center for the flourishing of culture and commerce during the Orientalizing Period was the city of Corinth located on the narrow isthmus connecting the Peloponnesus with mainland Greece. Due to its strategic location with ports accessing both the Aegean and Adriatic, Corinth became a rather lucrative port of trade for Syrian, Phoenician, and other Near Eastern merchants. Corinthians saw the influx of exotic metal ware and ivory trinkets, pottery designs, and elaborate textile patterns. Some scholars even think that Near Eastern artisans and craftsmen may have made their way over to Greece to ply their skills. The Greeks themselves began to travel more extensively to foreign lands, including great forays up and down the Nile of Egypt beginning in the mid 7th century. And all this exposure to foreign artistic motifs and conventions, long-standing monumental architecture of ancient civilizations, new stories, cultures, myths, and legends had a tremendous impact on the visual arts of Ancient Greece.

The artisans and consumers of Corinth had a particular appeal for the Near Eastern aesthetic, or at least their spin on what was seen as quote-unquote “Oriental.” While Athens continues to linger in the traditional Geometric vase painting design of the previous century, Corinth quickly pushes this aside in favor of new Oriental designs, like exotic chimeras and sphinxes, ferocious wild beasts and prey, and flowering rosettes and palmettes. The stark contrast of the darkly silhouetted Geometric figure against a background of meandering patterns, gives way to gentler curves and elaborate outlines of the figure’s contour with a smoother, flowing brush. Color also begins to make an appearance in Corinthian Orientalizing vase painting. You can clearly see the use of red, black, and white on the Art Institute pyxis. This pyxis also seems to display a sense of horror vaccui of the earlier Geometric Period. Every possible blank space on the background is strategically filled with some sort of rosette or linear pattern so as not to leave any large portion of undecorated surface.

What’s immediately most striking about this pyxis is, of course, the central decorative scene. In the very center we have a composite monster with the torso and legs of a lion, wings of an eagle, and head of a human female, known in Greeks mythology as the sphinx. This pyxis is attributed to the so-called “Ampersand Painter” because the shape of the sphinx’s tail is that of an ampersand (you know, the “and” symbol). This ampersand-shaped tail is the signature mark of this particular painter or workshop and it can be seen on other works in other museum also attributed to the Ampersand Painted. The earliest account of the sphinx in Greek myth comes from Hesiod’s Theogony, one of the earliest works of Greek literature, composed sometime in the late 8th to early 7th century BC. Hesiod briefly mentions the sphinx among his litany of the origins of all the myriads of hybrid monsters and creatures conjured up in Greek minds or imported by the Greeks from neighboring cultures and myths. Now, it’s hard to argue that the sphinx is a purely Greek invention when you’re faced with all the similar composite creatures of Near Eastern tradition that first started to make their way over to Greece around the time when Hesiod puts pen to paper, creatures like the lammasu, shedu, manticore, griffin, and chimera. But certainly the oriental influence contributes to the new forms of expression and experimentation, with both a profound interest in the ancient civilizations of the Near East and a new interest among the Greeks in their own ancient ancestry.

It’s around this time when the Greeks begin to look more closely at the remains of their own Bronze Age Mycenaean ancestors. At the same time when the great Homeric Epics of the Iliad and Odyssey were being recited, as the Greeks were weaving tales of the heroic warriors Achilles, Menelaus, and Agamemnon, so too were they looking out over the standing ruins of ancient Mycenae, the palace of King Agamemnon. There’s even evidence that the Dark Age and Archaic Greeks excavated Mycenaean tholos tombs, digging down to their entrances with their monumental Cyclopean masonry to establish shrines and offer votives at the tombs of these heroic warriors.

So where are we going with all of this? Well, the central sphinx is conventionally seen as some sort of Near Eastern or Oriental influence. Ok, I’ll buy that. Flanking the sphinx you’ve got a couple feline creatures usually interpreted as lions or leopards. Felines, particularly lions, are very prevalent throughout Ancient Near Eastern art in architectural relief from the walls of ancient Babylon and Persepolis to the smaller decorative arts. But I argue a very different and distinctly indigenous influence taking place here. See how the two lions have their bodies turned inward toward the central sphinx, but their faces gaze outward with giant, blank, piercing eyes fixed upon you, ferocious beasts of prey staring you down. I mentioned how the Greeks of this day and age were interested in exploring and rediscovering their own heroic and mythic past of the Bronze Age Mycenaean Civilization and that the ruins of Ancient Mycenae, the so-called palace of King Agamemnon were readily visible and available to the early Archaic Greeks. The most visually powerful and notable architectural remains at Mycenae is the well-known Lion’s Gate. Here we are confronted by two colossal lions, their muscular bodies rearing up on a central platform. Their faces are now lost and the dowel holes suggest that they were carved separately. The way the dowel holes are positioned and the form of what’s remaining lead most scholars to believe that the faces were likely turned to gaze outward, staring down at the lowly people passing underneath the monumental gateway. Throughout Ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern cultures and even well beyond into the Middle Ages of Europe, lions are a common emblem of kingship. The effect of this in-your-face confrontation by these gargantuan beasts conditions the viewers approaching the gate. The Lion’s Gate conveys this message of “Beware! Know that the king within is as mighty as a lion.”

The Lion’s Gate was in plain sight of the Greeks. In the day when monumental art, sculpture, and architecture reemerge from a long period of dormancy, it’s not surprising that they’d look back to their country’s former glory while also incorporating ideas and motifs from exotic civilizations abroad. In the mid 7th century BC the Greeks began creating their first monumental temples in stone. Perhaps the earliest known stone temple in Greece is that of Apollo at Corinth with a date somewhere between 670 and 630 BC. And in a couple generations, the Greeks settled on the sort of temples we think of when we think of Greek temples, with the surrounding columns called a peristyle, the pitched roof, and triangular pediment, all that sculpture above the east and west sides. The earliest known Greek temple of this style is the one to Artemis on the island of Corfu, just off the western coast of Greece. Built around 580 BC, right around the time when the Art Institute’s pyxis was created, the temple of Artemis displayed a magnificent pediment with a sculptural motif that should be pretty familiar to us by now. Seen from their sides, two great cats poise with their muscular bodies ready to pounce. Their faces are turned outward, just as in the Lion’s Gate, gazing at the tiny worshippers below as they make their approach to the house of the maiden huntress Artemis. In the center of the pediment between the lions stands the Gorgon Medusa, a fiendish creature with snakes for hair, said to be so ugly that her gaze would transform you to stone. This presentation of otherworldly ferocity and might is certainly something to give you goose-bumps, if you were an Ancient Greek not used to seeing such incredible displays nor desensitized by modern horror flicks.

And moving along to our darling little pyxis, the Ampersand Painter seems to have jumped on the bandwagon of Orientalism and Mycenaean revivalism (and that’s not a real term. As far as I know, I just made it up.) But why use this confrontational lion motif that might otherwise be more appropriate for temples and royal palaces? I don’t think the message here is “Beware the cosmetics housed within!” No, more likely it’s just meant to give us a little moment to pause … a jarring experience (ugh … pardon the pun). Remember, what we’re looking at here, as with most Ancient Greek ceramics throughout museum collections, is a grave good, something buried with the recently departed. This vessel exists because someone has died. While a pyxis for the living might be plain or decorated with little flowers and prancing deer, this vessel for the dead has a confrontational gaze inducing a moment to pause and reflect. A memento mori. A reminder of our own mortality.

On that cheerful note …

Thanks for listening. And don’t forget to swing by the website, scarabsolutions.com for additional resources, an extensive bibliography on ancient art and civilization, photos, and links to great external resources. And most recently, I’ve added a link that’ll let you subscribe to the podcast in MP4 format, so you can play it with images on just about any digital media player. Check out the website for more details. Take care, stay warm, and see you next time on the SCARABsolutions Ancient Art Podcast.

©2007 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org