[AFG_gallery id=’4′]

Hello and welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast, pumping straight into your soft brain matter since 2006. I’m the cerebral spelunker of antiquity, Lucas Livingston.

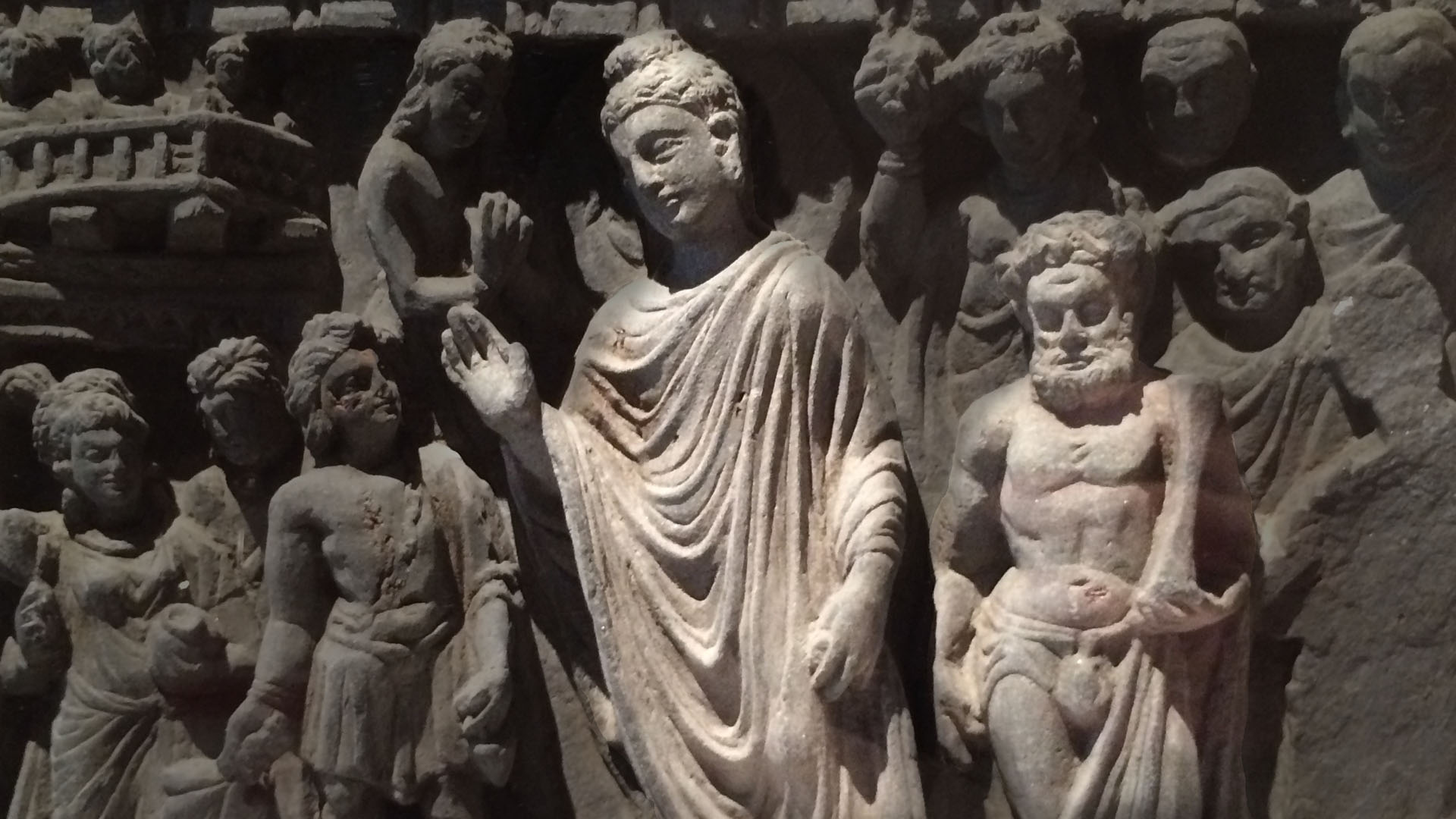

Last time in episode 67 we learned all about a Buddhist relief carving in the Art Institute of Chicago. It has a really long name. It’s called a “Relief with Buddha Shakyamuni Meditating in the Indrashala Cave (top) and Buddha Dipankara (bottom).” We met the two Buddhas depicted here, Shakyamuni and Dipankara, and found out that the story on the bottom presages the narrative on top. For the full picture, be sure to go back and check out episode 67, “Buddha’s Past Lives – Dipankara and Shakyamuni” at http://ancientartpodcast.org/67. Now the promised bombshell. The reason you all came back. This muscular, shaggy-bearded, club-wielding brute next to Buddha. Why in the world in a Buddhist work of art does the legendary Greek hero Hercules make an appearance?

Remember, this is a nearly 2,000 year-old work from the ancient Gandharan kingdom, present day Pakistan and Afghanistan. We’ve looked at Gandharan art repeatedly in the podcast, because I’m a big fan of it and I’m steering this ship.

This is the perfect storm of time and place where east meets west, where cultures and faiths collide in the multi-century long wake of the campaigns of Alexander the Great and his Greek successors. It’s a melting pot of Silk Road merchants, itinerant monks, and diplomatic envoys from Parthia and Sassania to the west, the Chinese Han dynasty to the north, and Indian kings to the south. The Gandharans were the successors to centuries of Greek rule under the Seleucids, the Greco-Bactrian kings, and the Indo-Greek kings. The artistic style is commonly called Greco-Buddhist by art historians today.

Many Greek images, stories, and customs blended with the early evolving Buddhist traditions of Gandhara, such as, frankly, representing gods in human form (and that includes Buddha) and also the inclusion of Hercules as none other than the body guard of Buddha.

In Greek mythology, Hercules was a great protector of mankind against forces of evil. He slew the murderous Nemean Lion. He vanquished the venomous multi-headed hydra. He traveled the world in search of the apples of Hesperides and even fought his way through the Greek Hell, Hades, to wrestle and kidnap the bloodthirsty, three-headed hellhound Cerberus. And he did all of these tasks at the bequest of a king named Eurystheus. Hercules was a supporter of kings. He was considered the ancestor of the Macedonian dynasty of kings. Alexander the Great had the image of Hercules struck on his coins. Many Hellenistic kings after Alexander included the image of Hercules or increasingly of Alexander dressed as Hercules as a way of saying, “See, I have the support of Hercules. I am the new Alexander.”

As the Gandharan region transitioned from Greek to Buddhist rule, the vocabulary of leadership wasn’t wholly reinvented. But in this new Buddhist world of selflessness — and I’m tossing around that deeply philosophical term fairly casually — in this new world, it wasn’t the king who was supported by Hercules, but Buddha, the new overarching king and figurehead. Through his Twelve Labors, Hercules was also a famous wanderer, as was the Buddha, so they were just two peas in a pod.

This role of Hercules as the bodyguard of Buddha seems to have originated in Gandhara and spread out from there. [1] He was considered a bodhisattva and given the name Vajrapani, meaning “He, who holds the ‘vajra’ in his hand.” We know the vajra. We learned all about it in episode 17 with Kartikeya, god of war seated on his peacock. The vajra is the thunderbolt, a weapon used to defend the Buddhist way. And thanks to episode 7 about the Art Institute’s statue of a Gandharan bodhisattva, we know what a bodhisattva is — like a Buddhist Saint. Some heavily hellenized Gandharan representations depict Hercules with his requisite knobby club, while others may eschew that convention for a more eastern-looking vajra thunderbolt scepter. As the image of Vajrapani travels away from the Greco-Buddhist Gandharan tradition in both time and place, he deftly adapts to a regional appearance. In China, Vajrapani becomes the patron saint of the Shaolin monastery. And in China the lion skin cloak of Hercules makes no sense, so Vajrapani is given a tiger skin cloak instead. Ah, that’s better.

As he moves further east, we see Vajrapani developing a distinctly Japanese personality, being identified with the “Nio,” guardians standing at the entrances to Buddhist temples. The Nio have a conspicuously muscular build with fiercely combative expressions. Their ferocity frightens away evil spirits and unruly vices that would corrupt us and hinder our Buddhist journey to salvation. One popular Nio has the name “Shukongojin.” That translates literally as the “Vajra-wielding God,” though conventionally we refer to him as the “Thunderbolt Deity.” “Shukongojin” and “Vajrapani” both basically mean the same thing: “the one who holds the vajra,” or once upon a time the knobby club of Hercules. Incidentally, if you plug the kanji characters for “kongo” (金剛) into Google Translate, you get “King Kong.”

And lastly we find another class of Buddhist deities similar to Nios called Wisdom Kings. In Sanskrit that’s “Vidyaraja,” “Mingwang” in Chinese , “Myō-ō” in Japanese, and in Tibetan Buddhism they’re called “Herukas.” By golly it’s tempting for me to see the name “Hercules” in the Tibetan word “Herukas,” but that’s pure conjecture on my part and I’m sure any true Tibetan scholar could set me straight.

But still, hopefully your mind is blown, because I know mine is. Just think about it. We’ve followed the long journey of Hercules from the Grecian Mediterranean to the Buddhist temples of Japan seeing him adapt and mutate as the master of disguise and the ultimate superhero defender of righteousness.

Thanks for tuning in to the Ancient Art Podcast. If you dig the podcast, please consider leaving a little something in the tip jar. Just head on over to ancientartpodcast.org and click on the juicy “Donate” button. Any amount helps me pay for bandwidth and keep’n it real! And if you can’t spare a schilling, how about a nice five star rating and some comments on iTunes, subscribe, thumbs up, and share my YouTube channel, like and share the podcast on Facebook at facebook.com/ancientartpodcast, and follow me on Twitter @lucaslivingston. If you wanna drop me a line, go to ancientartpodcast.org/feedback or email me at info@ancientartpodcast.org.

Thanks and see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

[1] For a discussion that Hercules effectively replaced Indra in the role of supporter of Buddha, see Katsumi Tanabe, “Why is the Buddha Sākyamuni Accompanied by Hercules/Vajrapāni? Farewell to Yaksa-theory,” East and West, Vol. 55, No. 1/4 (December 2005), 363-381.

2 Replies to “68: Hercules and Buddha Walk into a Bar”