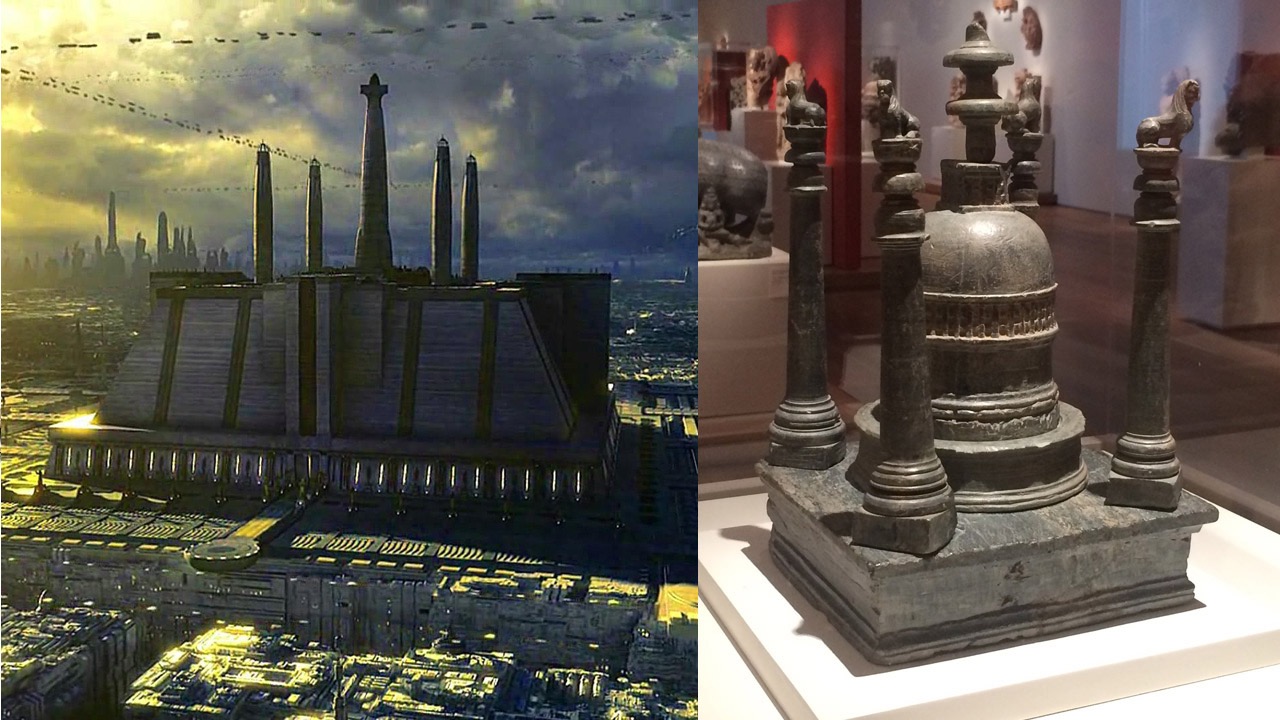

66: Star Wars and Stupas

Welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m Lucas Livingston. We’re picking up where we left off with the Gandharan Stupa Reliquary in the Art Institute of Chicago. You’ll want to be sure to check out that episode first if you’re not already familiar with what a Gandharan stupa reliquary is. This episode tells us a little bit more about its time period, the four pillars around the dome, and maybe a little something else fun. Continue reading “66: Star Wars and Stupas”

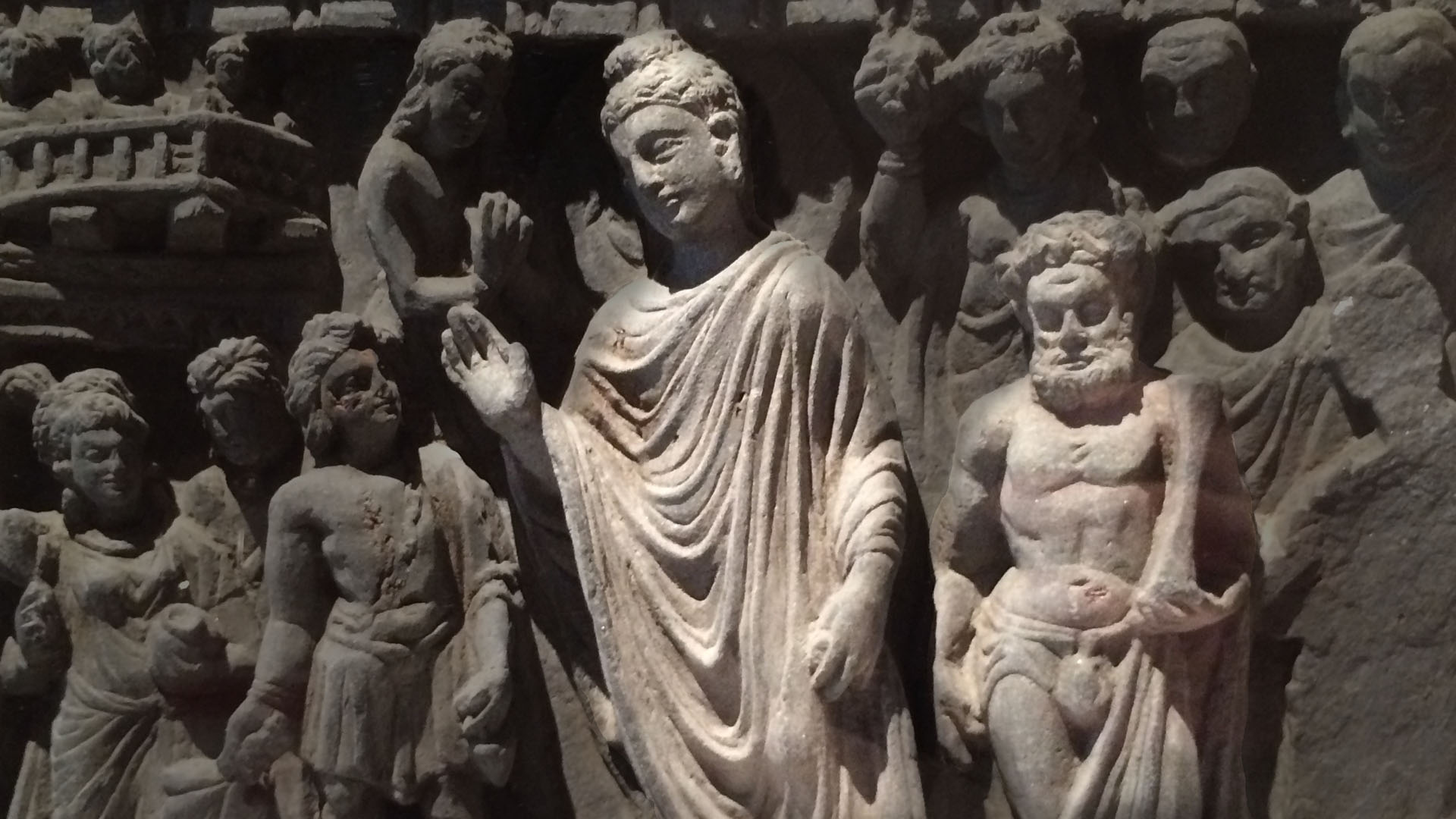

65: Gandharan Stupa Reliquary

20: Ancient Olympics, Part 3

Alright, welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. It’s time to wrap things with part 3 of the Ancient Olympics. We looked at the foundation myths for the four major crown games at Delphi, Nemea, Isthmia, and Olympia. We also, ahem, exposed the concept of nudity as a quintessentially democratic Greek dynamic to ancient athletics. This time we’re getting in to the nitty gritty where we can smell the sweat and taste the dirt. Ancient athletics never felt so real. We’ll keep looking at what makes the Greek games essentially Greek and we’ll run through a survey of the different types of athletic events at the Olympics. Then we’ll go on a nice little marathon run and polish things off with some character portraits of notable athletes.

Like nudity, explored in episode 19, another fascinating quality to the ancient Greek games, which contributed to their idealized democratic nature, was how judging took place. All subjectivity was removed from judging. There were no points awarded for grace or form. Judging was done using objective standards. Who hurled the javelin furthest, who ran the fastest, or who threw his opponent to the ground first. Judges are fairly easy to spot in Greek vase painting. Just look for the guy with the big stick. We see judges calling matches to an end when a victor is declared, or sometimes intervening in a match when a contestant breaks the rules. The beauty of competing in the nude — no, this isn’t going where you think — but it’s that the aristocrat and laborer were judged alike and judgment was swift and harsh.

Most of the events of the Ancient Olympic Games are familiar to us. The earliest type of event, the only event that would have been held at the supposed first Olympiad of 776 BC, was the stadion, from which we get the word “stadium.” The stadion was basically just the ancient equivalent to the 200 meter dash. Contestants would run down the length of the stadium, which was 600 ancient feet. Funny thing is, though, the official length of a foot varied from location to location. The length of the stadium at Olympia was different from the length at Delphi, Isthmia, and Nemea. But that sort of standardization didn’t really matter to the ancient Greeks. Another footrace that was added to the Olympics in 520 BC was the hoplitodromos, where athletes would run down the stadium and back in armor, wearing helmets and greaves, and carrying shields. Again, there’s no evidence that there was any sort of standardization to the weight of the armor being carried. Similarly, in the pentathlon, one event was the long jump. Athletes would often jump with the aid of handheld weights called halteres, or halters. Halters have been excavated from different sites and periods and there’s no apparent pattern to their shape or weight. Much like a bowling ball, you’d use whatever weight works best for you. The other four events of the pentathlon, which originated in 708 BC, included the discus, the javelin, the stadion, and wrestling. You might think that’s where we get modern Greco-Roman wrestling from, but that’s just Victorian nostalgia run amok.

Similar to wrestling was another full contact event called pankration, literally “all-powerful,” the no-holds-barred ancient equivalent to mixed martial arts or the Ultimate Fighting Championship. The only illegal moves in the pankration were gouging and biting. Everything else was fair game. The idea for these rules comes from Hercules’s battle against the Nemean Lion. The lion’s hide was impenetrable to sword and spear, so Hercules was forced to grapple with it, choking the beast to death. Now, the pankration was not by definition a death match, but yes, some contestants did die. One of the most well known is Arrhichion of Phigaleia, pankration victor of the 572 and 568 Olympics. In his third attempt at an Olympic victory in 564, his opponent managed to get a good strangle hold on Arrhichion, slowly choking the life from him. But as darkness swept over him and the sleep of death crept in, Arrhichion swiftly executed one final move to wrench his opponent’s ankle from its socket. His opponent, still applying the choke hold, signaled submission to the judge. Arrhichion simultaneously became a three-time Olympic victor and slipped away into death.

We also see boxing, called “pyx,” added to the Olympics in 668 BC. And to round out the gymnikos agon, the nude games, we see the diaulos added in 724 BC. The diaulos was the second event added to the Olympics, after the stadion. Diaulos is the word for a double-flute, a common instrument from Ancient Greece. Playing on that term, the diaulos race was a double stadion, or down and back, just like the later hoplitodromos. And at the next Olympiad four years later in 720 BC, we see the addition of the dolichos, the long-distance run, somewhere around 20 to 24 laps of the stadium. It’s interesting that you can identify which race is being depicted in art based on the position of the runners’ knees and arms. If their arms are raised high up with knees high in long strides, they’re running the shorter stadion. If their knees aren’t quite as high, it’s likely the diaulos. Arms carefully tucked in to the torso like jogging, that’s certainly the long-distance dolichos. But if you’re not sure, inscriptions next to the runners sometimes provide additional evidence.

What about the marathon, you ask? The famed 26.2 mile run popular throughout the world today named after the famous ancient Greek site of the Battle of Marathon? You might be surprised to know that there was no such thing as the marathon run in the ancient world. It’s an entirely modern invention. The idea of the marathon originates from two possible stories that may have gotten mixed together in later times. The Battle of Marathon was a major Greek victory over the Persians in 490 BC. The basic story is that the Athenians sent a messenger named Pheidippides to run from Marathon to Athens after the battle to announce their victory. As soon as he arrived and shared the news, he dropped dead. But there’s no mention by Herodotus in his contemporary account of the Battle of Marathon of anyone running from Marathon to Athens to deliver the news. He does mention a messenger named Pheidippides or sometimes Philippides in some manuscripts, who ran from Athens to Sparta before the battle to seek Spartan aid. The other story that gets mixed with Herodotus’s is that the Athenian hoplite force, after defeating the Persian army at Marathon, marched at a high pace in full armor the 25 or so miles all the way from Marathon to Athens to defeat a second wave of the Persian attack. So, as I said, these two stories of two different runs eventually get mixed together to form the much more romantic account of Pheidippides, his valor, and his tragic self-sacrifice to bring news of the victory of democractic Greek heroism over the barbaric imperialism of Persia at the Battle of Marathon.

And the marathon run itself? Yeah, that was invented for the first modern Olympics in 1896 in an attempt to echo the legendary glory of Ancient Greece. As a side note, the distance was eventually standardized to 26 miles and 385 yards after the 1908 London Olympics. Today’s marathon run is not the distance from Marathon to Athens, but the distance from Windsor Castle to the royal box at the London Olympic stadium.

We’ve talked a lot about the gymnikos agon, the nude events, but what about the hippikos agon. I already mentioned that, despite all the hooplah about chariot races in art and literature nearly as far back as the Greek Dark Ages, they weren’t officially part of the Olympics until 680 BC. The first horse race to be added was the tethrippon, the four-horse chariot race, which was 12 laps around the hippodrome. But, of course, it shouldn’t surprise you any more that the length of the hippodrome wasn’t standardized from location to location. We also find the synoris, a two-horse chariot race, and the keles, a mounted horse race. As with today, it was advantageous to have as small and light a jockey as possible, but back in Ancient Greece that usually meant having a young slave boy race your prize horse. This silver coin from the Art Institute of Chicago commemorates the keles race won by Philip II of Macedon in 356 BC, father of Alexander the Great. The youthful jockey holds a palm branch, a secondary victory trophy given out at the games by this time. Philip’s name is stamped on the coin fragmented by the horse’s head. And on the other side (technically the obverse, if you want to talk numismatics) we see the god Zeus, the ultimate victor at the Olympics. Don’t forget — he’s the reason for the season.

Despite all this talk about the Olympics being the ultimate emblem of Greek democracy, there was definitely a social divide among the competitors and events. While any decent athlete could compete in the nude events, the horse races always held a certain air of snobbery and elitism. To enter in the horse races, one had to be able to afford a horse, chariot, rider, and training, which only the wealthiest of Greeks could afford. Last time in episode 19, we saw in the funeral games of Patroklos in Book 23 of the Iliad that Odysseus excelled in the footrace and wrestling match. Interestingly, though, he doesn’t compete in the chariot race, perhaps because he is one of the less affluent Greek kings at Troy and couldn’t afford to lug a team of race horses and chariot with him on a military campaign.

But this social divide didn’t prevent the masses from reveling in the spectacle of the horse races. By all accounts they were extremely popular. Popular for the masses and also as a means for political maneuvering and exploitation. The coin commemorating Philip’s keles victory ensured his fame and name would be dispersed throughout much of the Greek world. As Philip expands his outreach, he gains control of game sites, maneuvering to unify all of Greece in part through athletic competition, not as a series of disparate sacred centers and city states, but as a united nation of Hellenic people.

Hopefully this trilogy of episodes on the Ancient Olympics has whetted your appetite to delve a little deeper. If you’d like to learn more, visit the bibliography in the Additional Resources section at ancientartpodcast.org, where you’ll find a section under Greece on “the Olympics and Other Greek Games.”

©2009 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org