Hi friends. This is Lucas Livingston. As you may know, the Ancient Art Podcast is a labor of love with a staff of one and a budget of zero. If you enjoy the podcast and want to see it continue, I encourage you to consider offering a donation. Whatever you think the podcast has been worth to you over the years. Whether it’s $1 or more, your donations help me pay for web hosting, bandwidth, and “keepin’ it real.” Just visit ancientartpodcast.org and click on the “Donate” button. Another way to help is if you’d please consider giving the Ancient Art Podcast a juicy 5-star rating in iTunes, write some nice comments, and give it a big thumbs up in YouTube. Thanks for tuning in and thanks for your support.

Greetings friends and welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m the kibble to your bits, Lucas Livingston. Dogs in their myriad of pedigrees are so integrated with our modern society that it’s easy to overlook how integral dogs were to ancient civilizations. The artistic, archaeological, and literary records of our ancestors can shed some light on their trusty companions and might even make the ancient world seem just a little bit more human to us. “Human,” sure. “Humane?” Well, let’s see about that.

In this episode, we’ll touch on just one example of canines in ancient art, but conceivably one of the most popular, the Colima dog of ancient West Mexico. But don’t fret, canine lovers, as I have future episodes already in the oven that sink their teeth into our canine companions from ancient China and the Greco-Roman World. Why all the culinary metaphors? Well, this leads us into our story.

This happy, pudgy pup in the Art Institute of Chicago is an exemplary specimen on one of the most frequently occurring examples of canines in ancient art, the ceramic Colima dog. Looking at this dog, with its rotund, squat body and stubby legs, you may be reasonably safe in speculating that it didn’t serve as a guard dog or a hunting dog. In fact there aren’t too many jobs a dog of this sort could have had in real life other than perhaps a friendly companion or as the main course slathered in barbecue sauce with a side of corn bread.

This happy, pudgy pup in the Art Institute of Chicago is an exemplary specimen on one of the most frequently occurring examples of canines in ancient art, the ceramic Colima dog. Looking at this dog, with its rotund, squat body and stubby legs, you may be reasonably safe in speculating that it didn’t serve as a guard dog or a hunting dog. In fact there aren’t too many jobs a dog of this sort could have had in real life other than perhaps a friendly companion or as the main course slathered in barbecue sauce with a side of corn bread.

Insensitive and appalling as that may seem to dog enthusiasts today, dog was the daily special on the menu throughout ancient Mesoamerica. [1] Small to mid-sized hairless dog breeds are found in multiple ancient and modern cultures across the Americas. While these dogs served a variety of roles, livestock was indeed among them. And it can actually make sense, when you think about it. Unlike in the old world across the pond, where we find sheep, cattle, pig, goat, chicken, and many other domesticated sources of animal protein, in Mexico and Central and South America dogs are pretty much the only indigenous domesticated source of protein. [2] And the popularity of the animal manifests in the arts.

In the ancient west Mexican Colima culture of about 2,000 years ago, we find ceramic dog figures in 75-90% of the shaft tombs. [3] The body type reflected in the Art Institute’s example would seem ideal for maximum protein yield for minimum calorie investment. You might call it something like a “designer pig.”

In the ancient west Mexican Colima culture of about 2,000 years ago, we find ceramic dog figures in 75-90% of the shaft tombs. [3] The body type reflected in the Art Institute’s example would seem ideal for maximum protein yield for minimum calorie investment. You might call it something like a “designer pig.”

Colima dog sculptures may have been popular funerary effigies as an offering of food for the deceased’s journey in the underworld. (I should note that I’m showing remarkable restraint by not including an image of a Colima sculpture of roasted dog on a serving platter. [4]) Yet the Colima dog must have been regarded as more than just a food source.  Surreal images of dogs waltzing, wearing turtle and armadillo shells, and with human-faced masks indicate a symbolic and spiritual significance. [5] Myths and legends of dogs abound in Mesoamerican cultures, including the predominant belief that dogs served as guides for the soul in the afterlife. [6] Legends tell us of a spirit dog that the recently deceased would encounter. It’s said that you should take hold of the dog’s tail so it can shepherd you across a body of water into the hereafter. [7] A central Mexican legend says that if you treat your dog right in life, it will meet you in death as a guide. [8] Another legend of central west Mexican coastal culture informs us that a snarling dog will meet you in afterlife, but it’s easily pacified with a few tortillas, so tortillas are in fact a common burial good in this culture. [9]

Surreal images of dogs waltzing, wearing turtle and armadillo shells, and with human-faced masks indicate a symbolic and spiritual significance. [5] Myths and legends of dogs abound in Mesoamerican cultures, including the predominant belief that dogs served as guides for the soul in the afterlife. [6] Legends tell us of a spirit dog that the recently deceased would encounter. It’s said that you should take hold of the dog’s tail so it can shepherd you across a body of water into the hereafter. [7] A central Mexican legend says that if you treat your dog right in life, it will meet you in death as a guide. [8] Another legend of central west Mexican coastal culture informs us that a snarling dog will meet you in afterlife, but it’s easily pacified with a few tortillas, so tortillas are in fact a common burial good in this culture. [9]

The Peruvian and Mexican hairless breeds today come in toy, miniature, and standard sizes. [10] The Mexican hairless, or Xoloitzcuintli, has even been making a splash lately at the Westminster dog show. [11] The name Xoloitzcuintli is variously translated from the Aztec language, including “strangely formed dog.” [12] It’s also associated with the Aztec god Xolotl, god of fire and death, and “itzcuintli,” Aztec for “dog.”

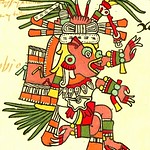

The Peruvian and Mexican hairless breeds today come in toy, miniature, and standard sizes. [10] The Mexican hairless, or Xoloitzcuintli, has even been making a splash lately at the Westminster dog show. [11] The name Xoloitzcuintli is variously translated from the Aztec language, including “strangely formed dog.” [12] It’s also associated with the Aztec god Xolotl, god of fire and death, and “itzcuintli,” Aztec for “dog.”  Xolotl is the brother of Quetzalcoatl and sometimes appears as a dog-headed man. At a time when human diversity was embraced differently, Xolotl was also the god of deformities, hence the association with the curious hairless breed.

Xolotl is the brother of Quetzalcoatl and sometimes appears as a dog-headed man. At a time when human diversity was embraced differently, Xolotl was also the god of deformities, hence the association with the curious hairless breed.

Full disclosure, though, I have to confess that our discussion here of the Colima dog and Xoloitzcuintli is entirely selfish, motivated by homage for my own little Xolo pup, Sputnik. So while his ancestors may have been couriers of the dearly departed or finger-licking comfort food, I think they would smile on his upgraded social status, having evolved from fork to friend.

Thanks for tuning in. If you want to do some more digging on the topic of dogs in ancient Mesoamerica, check out http://ancientartpodcast.org/61 and look in the footnotes to the transcript. There you’ll also find a gallery for images used in this episode with their sources and credits. You should also visit my Flickr site (just click on the Flickr logo at http://ancientartpodcast.org) where you’ll find photo sets dedicated to each of the podcast episodes and a plethora of other photos I’ve taken over the years, including when the Art Institute of Chicago sent me along as a study leader on trips to Egypt, Jordan, Greece, and Turkey.

If you dig the Ancient Art Podcast, be sure to “like” us on Facebook at facebook.com/ancientartpodcast and give us a nice 5-star rating on iTunes. You can follow me on Twitter @lucaslivingston and can subscribe to the podcast on YouTube, iTunes, and Vimeo, where you’ll hopefully give us a good rating and leave you comments. You can also email your questions and comments to me at info@ancientartpodcast.org or use the online form at http://feedback.ancientartpodcast.org. Thanks for tuning in and see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2014 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[1] Jarrett A. Lobell, Eric A. Powell and Paul Nicholson, “More than Man’s Best Friend,” Archaeology, Vol. 63, No. 5 (September/October 2010), p. 26-35.

[2] See note 1. Archaeology (September/October 2010), sidebar: “Dogs as Food,” p. 32.

[3] Heritage of Power: Ancient Sculpture from West Mexico: The Andrall E. Pearson Family Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 67.

Jacki Gallagher, Companions of the Dead: Ceramic Tomb Sculptures from Ancient West Mexico, p. 41.

[4] Ancient West Mexico: Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past, p. 212, fig. 29.

[5] Ancient West Mexico: Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past, p. 185, 211.

Jacki Gallagher, Companions of the Dead: Ceramic Tomb Sculptures from Ancient West Mexico, fig. 69.

[6] Ancient West Mexico: Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past, p. 272.

[7] See note 1. Archaeology (September/October 2010), sidebar: “Guardians of Souls,” p. 35.

[8] Ancient West Mexico: Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past, p. 186.

[9] Heritage of Power: Ancient Sculpture from West Mexico: The Andrall E. Pearson Family Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 66.

[10] The Westminster Kennel Club | Breed Information: Xoloitzcuintli. Accessed 13 May, 2014.

[11] Westminster Dog Show: Introducing The Xoloitzcuintli. NPR. Accessed 13 May, 2014.

[12] Ancient West Mexico: Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past, p. 272.

———————————————————

See the Photo Gallery for detailed photo credits.

Credits:

2 Replies to “61: Dogs in Antiquity: Xoloitzcuintli & Colima”