Hello and welcome back to the SCARABsolutions Ancient Art Podcast, your guidebook to the art and culture of the Ancient Mediterranean World. I’m your host Lucas Livingston.

In our second podcast episode on the Mummy Case of Paankhenamun, I mentioned that the Art Institute has a really nifty statue of Osiris, the kind of statue that you’d commonly find in the burial chambers of well-to-do Ancient Egyptians. In this episode, I want to take a closer look at this statue and see how it fits in to the broad context of Egyptian funerary practice and ideology.

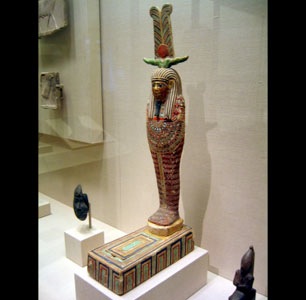

Here we have a statue of the Egyptian god Osiris, king of the gods, god of the dead, and lord of the underworld. This statue is dated to Ptolemaic Period, the time between the deaths of Alexander the Great in 332 BC and Cleopatra in 30 BC, when Egypt was ruled by a line of Macedonian Greek Pharaohs. It’s really during the earlier Late Period of Ancient Egypt when this statue type becomes common. You might more frequently encounter a statue of this type referred to as Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, a later composite form of god similar to Osiris, but incorporating aspects of the cults of Ptah, the ancient creator god of Memphis, and Sokar, and somewhat lesser known god of … nebulous origin. Sokar seems also to come from Memphis and was already associated with Osiris way back in the Old Kingdom and with Ptah even earlier.

When I say that this is a common type of statue, just what is it that makes up this “type?” Well, you’ve got the tightly bound mummy of Osiris standing upright on a large rectangular base that juts pretty far out in front of him. The base of this figure, as with many of its companions, is hollowed out to form a little cavity that would contain a scrap of papyrus with a spell from the Book of the Dead or a miniature mummy figure somewhat inappropriately referred to as a “corn mummy.” I’ll say a little more on that later. Sometimes the base isn’t hollowed out, but the statue itself is and then the little papyrus scroll is rolled up and shoved inside.

Also characteristic of this statue type is the crown that Osiris wears. You come across a variety of different crowns on Osiris, but the popular one for this figure is the twin-plumed crown with solar disk and ram horns, like the one we encountered on the anthropomorphic Osirid djed pillar on the mummy case of Paankhenamun.

But this Osiris statue at the Art Institute’s collection is a real beauty. I’ll give you a little challenge. You just try to find a more exquisite statue of this type and if you think you’ve found one, then drop me an email at scarabsolutions@mac.com. The artist has chosen a pretty diverse palette here including various reds, greens, blues, white, and yellow pigment, and gold leaf. The choice of colors might remind you of Paankhenamun. Similarly the gilding of his face. The skin of the gods in Ancient Egypt was said to be made of gold, so Osiris is shown that way here and Paankhenamun was appropriately represented similarly on his mummy case, when upon death he joins the pantheon and is identified with Osiris. Now, just to set the record straight, the mummy case and the statue of Osiris come from completely different tombs and completely different times. This figure comes from the tomb of a woman centuries after Paankhenamun. We know her only by her name from the inscription on this figure. Her name is Wsr-ir-des, which translates into something like “Osiris made her.” The inscription is a similar, but much later version of the offering prayer that we already encountered on the wall fragment from the tomb of Amenemhet.

The decoration of Osiris’s body is particularly exquisite with the elaborate netting meant to resemble detailed beadwork that may have originally adorned the mummy of Wsr-ir-des. An incredible necklace adorns his chest with rows of beautiful rosettes and lotus blossoms and items that may represent polished gemstones, tear-drop-shaped rubies and lapis lazuli. Falcon heads with solar disks suspend the necklace at either side, clasping it together in back. As with the beaded netting, the necklace was perhaps based on an original example that may have accompanied Wsr-ir-des in her tomb or could have previously been known to the artist.

We discussed in the earlier episode on Paankhenamun how the pedestal that the djed pillar stands on looks like a doorway, reminiscent of the niched façade of early royal tombs and the surrounding walls to mortuary temples. This niched façade motif shows up all over in Egyptian art and architecture, going back as far as Egyptian history itself. One of the earliest examples is even seen on the Narmer Palette, the ceremonial plaque traditionally interpreted as commemorating the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first king, Narmer. This little design is called a serekh, which is kinda like an early version of the cartouche, the emblem that surrounds and designates the king’s name. With its niched architectural façade pattern, it can be read symbolically as the gateway to the royal palace, literally housing the name, while figuratively housing the king. Later during the Old Kingdom this niched motif is seen in the surrounding perimeter wall of the mortuary temple and pyramid complex of King Djozer. The niched façade motif quickly takes on a funerary context and as funerary art and architecture evolves, we see it being used a little differently. Sarcophagi adopt a distinctly architectural appearance, incorporating the niched façade pattern and cavetto cornice (that curved eaves at the top), seen here in a line drawing of the sarcophagus of King Menkaura, now somewhere at the bottom of the Mediterranean.

During the First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom, as private individuals begin to participate in the luxury of elaborate funerary rites, the niched façade motif begins to show up decorating the exterior of coffins. Here’s one Middle Kingdom example from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Coffin of Khnum-nakht. Beautifully detailed hieroglyphic bands of funerary spells and invocations form the decorative pattern of the niched façade. The architectural idea of the coffin is further elaborated with the appearance of a false door, which would originally decorate a wall in the offering chamber of the deceased as a spiritual doorway through which the decedent’s ka emerges to receive the nourishment of the offerings left behind. The false door itself also repeats the niched pattern, suggesting the grand entry of an Old Kingdom royal mortuary temple. Above the false door we see two eyes staring out, the Eyes of Horus, through which the deceased can look out to observe the people bringing offerings. Now, once Khnum-nakht was interred and his tomb sealed, people wouldn’t be able to see the coffin, but he likely had an attached chapel with a false door and offering scene, perhaps with the Eyes of Horus, where one would leave offerings for his ka.

Here, for example, is one such offering scene that may have decorated the panel area above a false door, similar to the wall fragment that we looked at in our earlier podcast on the Mummy Case of Paankhenamun. Both come from the Middle Kingdom, when this was all the rage for the Egyptian nouveau riche. Not to be confused with the example from the earlier podcast, which shows Amenemhet with his wife Hemet and son Amenemhet, here we see Amenemhet (no relation) with his mother Yatu. And notice the Eyes of Horus above.

It took a few eons before the private individual could participate in all the pomp and circumstance of an elaborate funeral and burial, which previously had been reserved for royalty. This change takes place around the time of the First Intermediate Period after the collapse of the Old Kingdom. And then it took another eon or two before said individual could participate in the same rite of passage upon death, the Osiris resurrection mystery.

I already summarized the myth of Osiris’s murder, dismemberment, and resurrection. Osiris has always has a strong connection with death resurrection, and fertility, chiefly in an agrarian sense. This apparent contradiction of embodying both life and death didn’t seem to bother the Egyptians. We find what seem like contradictions and dichotomies throughout Egyptian mythology, which might make us scratch our head and wonder. But the Egyptians were never burdened by our Western tradition of Platonic logic. What we may perceive as a contradiction could have been perfectly alright to them. Getting back to Osiris, the Egyptians weren’t unique with their association of fertility, life, and death. We find a similar concept of a particular deity presiding over both life and death or creation and destruction in various cultures throughout history, like the Greek Demeter or Hindu Shiva, just to name a couple.

After Isis gathers up and puts together all the pieces of Osiris’s dismembered body, Osiris essentially becomes the first mummy and it’s in this state that he is almost always depicted, all tightly wrapped up. Being the first mummy, his murder arguably is also the first instance of death in Egyptian myth, and the first entombment. The ideas of life, death, fertility, entombment, and resurrection all come together in the statue of Osiris. The pedestal that Osiris stands on bears a striking resemblance to that Coffin of Khnum-nakht and the drawing of the sarcophagus of Menkaura. The pattern painted on the wooden base is meant to mimic the traditional niched pattern of early mortuary temple façades, Old Kingdom sarcophagi, Middle Kingdom coffins, and false doors. And just as there is always something further behind the façade, ultimately a mummy, here too as I briefly said earlier, we often find a little corn mummy under the trap door in the cavity of the box. I said that the corn mummy is a misnomer. That’s the case because there was no corn in Ancient Egypt. Corn is a New World crop. Egyptian grew a variety of other grains like barley and emmer, but not corn. Now, this is all semantics with a distinctly American bias. “Corn” is just the word used by English anthropologists to denote the staple crop of a region. Corn as it’s known to your average American is technically and more properly referred to as “maize.” So. The corn mummy is composed of earth and grain, the key ingredients, which when mixed with water, create life. Germination parallels resurrection, two distinct aspects of Osiris.

The corn mummy plays out in microcosm the whole ideology of death and resurrection in Ancient Egypt.

And kinda like a series of nested Russian dolls, we find the corn mummy within its tomb, which in the form of the Osiris statue is placed within the larger tomb of the deceased.

How’d-ya-like them apples!

As always, I encourage you to check out the website — scarabsolutions.com. If you’re listening this podcast in iTunes, you can just click on the link in the artwork display. I’ve added a couple useful links on the website. One to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which I talked about last time. The MFA has a great online database that lets you browse or search over a third of a million objects in its collection. And their collection of ancient art is something to be envied.

I’ve also added a link to the Met’s online collection, where you’ll find the Coffin of Khnum-nakht and a gazillion other works of art.

And in a year or two the Art Institute may also begin to participate in the 21st century by putting the bulk of its collection online in a searchable database with images.

I’ve also added a new section to the SCARABsolutions website featuring links to a few of my other favorite podcasts, which of course I highly recommend, including the Art Institute’s new MuseCast. So check it out, or just search the iTunes Store for the Art Institute of Chicago.

©2007 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

Ptaaah’, the sound of ejaculation. Ptooey

Isis was the virgin serpent goddess of double wisdom in Assur’s(Osiris) garden. Ergot was in the midst. Picking ergot out of your grain would have killed the ancients. The lowly serpent overruled God, she knew the antidote.

The Soma Sacrament in Egypt was imbibed in the form of bread and beer. They ate the “bread of eternity,” and drank the “beer of everlastingness.” The Eye of Heru was in the bread. The antidote was in the beer. The bread without the beer was poison. The beer without the bread was poison. The Eye of Heru, the Forbidden Fruit of the Bible, the bread of eternity and the beer of everlastingness of the Egyptians, and the original Bread and Wine Sacrament of early Christianity were all allusions to the “Soma Mystery” of the ancients.