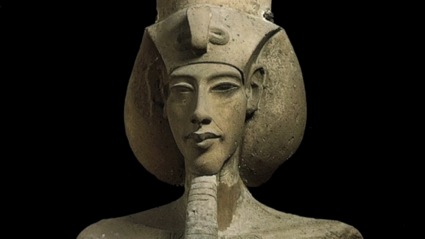

Greetings friendly companions and welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m Lucas Livingston, your Dungeon Master through this labyrinth of truth and fiction in our series of the Top 10 Ancient Egyptian Myths and Misconceptions. Counting down from ten to one, we come to number 5: “Akhenaten Was the World’s First Monotheist.” Many of us are likely pretty familiar with the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten, the so-called “Heretic King,” who ruled in the 18th dynasty from about 1353 to 1336 BC and radically transformed Egyptian national art and religion. We already gave some attention to whether or not Akhenaten was a monotheist back in episode 21 on “Akhenaten and the Amarna Style,” so this episode will serve mostly as a refresher. I encourage you to go back and listen to episode 21 in all its glory. The quick link to that episode is www.ancientartpodcast.org/episode21, or, of course, you’ll find it on YouTube, Vimeo, and iTunes.

To summarize the debate, it’s probably good to look at the pros and cons for Akhenaten being a monotheist. First the pros: Around the year 1350 BC, in the second or third year of his reign, he changed his name from Amunhotep IV to Akhenaten, showing a clear shift in preference away from the state god Amun to a new state god, the solar-disk Aten. Soon, he initiated a widespread oppression of Egypt’s many traditional cults, especially the cult and priesthood of Amun, closing their temples and rejecting all gods except the Aten. What might seem like a slam dunk supporting monotheism might be seen in the scripture of the day. The Great Hymn to Aten appears on the walls of the tomb of Ay, vizier of Akhenaten and puppet master/successor to King Tut during the short period of approximately 1327-23 BC. The Great Hymn refers to Aten as the “Sole God beside whom there is none,” and repeatedly mentions how the Aten alone is the sole creator of everything its heavenly rays touch. It may seem difficult to argue against that evidence.

As an interesting aside, the Great Hymn to Aten bears some resemblance to Psalm 104 from the Bible:

“The entire land sets out to work, all beasts browse on their herbs.” (Great Hymn to Aten)

“You cause the grass to grow for the cattle, and plants for people to use.” (Psalm 104:14)

“Trees, [and] herbs are sprouting, birds fly from their nests, their wings greeting your ka. All flocks frisk on their feet, all that fly up and alight, they live when you dawn for them.” (Great Hymn to Aten)

“By the streams the birds of the air have their habitation; they sing among the branches. From your lofty abode you water the mountains; the earth is satisfied with the fruit of your work.” (Psalm 104:12-13)

“When you set in the western lightland, earth is in darkness as if in death. … Every lion comes from its den, all the serpents bite; darkness hovers, earth is silent, as their maker rests in lightland.” (Great Hymn to Aten)

“You make darkness, and it is night, when all the animals of the forest come creeping out. The young lions roar for their prey, seeking their food from God. (Psalm 104:20-22)

And similar passages continue. That said, however, the Great Hymn to Aten is also very similar to the long literary tradition of Egyptian hymns to the sun god Ra, which likewise elevate Ra to supremacy above all other gods. And Egyptian hymns, in general, bear a similarity to Biblical psalms, but we’ll leave that discussion to Biblical scholars and philologists. [1]

Arguing against monotheism, we already just learned that the Great Hymn to Aten is similar to the literary tradition of hymns to the sun god Ra. Furthermore, Ra, Ra-Horakhty, and other gods like Hapy and Ma’at also show up in the Great Hymn. So, here and elsewhere, we see that other lesser gods were tolerated and, to a minor extent, included in religious practice in supportive roles. It’s speculated that the humble people of Egypt gave lip service to the Aten and tolerated the new religion, but they continued worshipping their traditional gods behind closed doors. [2] There’s abundant evidence of statuary to the traditional gods at Tel el Amarna, the site of the new and short-lived capital city of Akhenaten, called Akhetaten. [3] For what it’s worth, funerals and mummification continue during the reign of Akhenaten, but we don’t see a lot of evidence of its traditional connection with the myth of Osiris. [4] But again, behind closed doors, it was certainly acknowledged, since that was necessary to ensure immortality in the hereafter.

It’s also important to note that the Aten was not a new god. It’s mentioned in the opening of the 12th dynasty Tale of Sinuhe, hundreds of years earlier. [5] Akhenaten’s predecessor and father, Amenhotep III, elevated the Aten to the role of creator deity, equating it with Ra and Amun. If you look back to episode 21, we see a nice little summary of the prevailing theory behind Akhenaten’s radical heresy, so let’s just quote it here:

“Akhenaten wasn’t a monotheist; he was more like a henotheist. Henotheism is the worship of one god, while believing that others exist and can get a little bit of credit too. Even though Akhenaten preached that the Aten was the one and only god, his motivation was largely political, not religious or ideological. In the generations leading up to Akhenaten, the state cult of Amun had risen to such unprecedented heights that it almost came to eclipse the authority of Pharaoh. The temple was the administrative and financial center of Egypt, holding massive tracts of land and immense influence over all aspects of Egyptian society and national affairs. In an effort not to become a puppet of the temple, Amunhotep III, Akhenaten’s father, already started to take measures to return to the unquestionable authority of Pharaoh, and Akhenaten took it that much further.” (Ancient Art Podcast, Episode 21, “Akhenaten and the Amarna Style,” 7:46-8:52)

But after the death of Akhenaten, we see an almost immediate return to orthodoxy, Amun is reintroduced as the state god, royal iconography begins reverting, and Akhenaten’s trademark style of art, called the Amarna style, fades away, but lingers on in inspired works of the Post-Amarna Period.

Of course, as with everything on the Top 10 list of Egyptian myths and misconceptions, some people will continue to believe what they want regardless of the evidence and I’m not here to convince you. If people will continue to believe what they want even after the birth certificate is published and after May 21 comes and goes, then what’s stopping people from conjuring up what happened over 3,300 years ago?

Thanks for tuning in to the Ancient Art Podcast. Remember that you can check out the whole list of the Top 10 Ancient Egyptian Myths and Misconceptions at www.ancientartpodcast.org/top10/. There you can also access other past episodes, images, credits, transcripts, links to other great online resources, and recommended podcasts. Feedback can go to info@ancientartpodcast.org or browse on over to feedback.ancientartpodcast.org. And if you missed the rapture, well, get yourself some good karma and leave us a comment on iTunes. Keep in touch at facebook.com/ancientartpodcast and follow me on Twitter @lucaslivingston. Thanks and see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2011 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[1] Lichtheim, Miriam. Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume 2. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1975-76, p. 100, n. 3.

[2] Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen. Exhibition catalog edited by Rita E. Freed, Yvonne J. Markowitz and Sue H. D’Auria, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts in association with Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown, and Co., 1999, cat. 108.

[3] Ibid. cat. 179-85, p. 29.

[4] Ibid. cat. 237.

[5] Lichtheim, v. 1, p. 223.

———————————————————

Credits:

See the Photo Gallery for image credits.

This is cool!