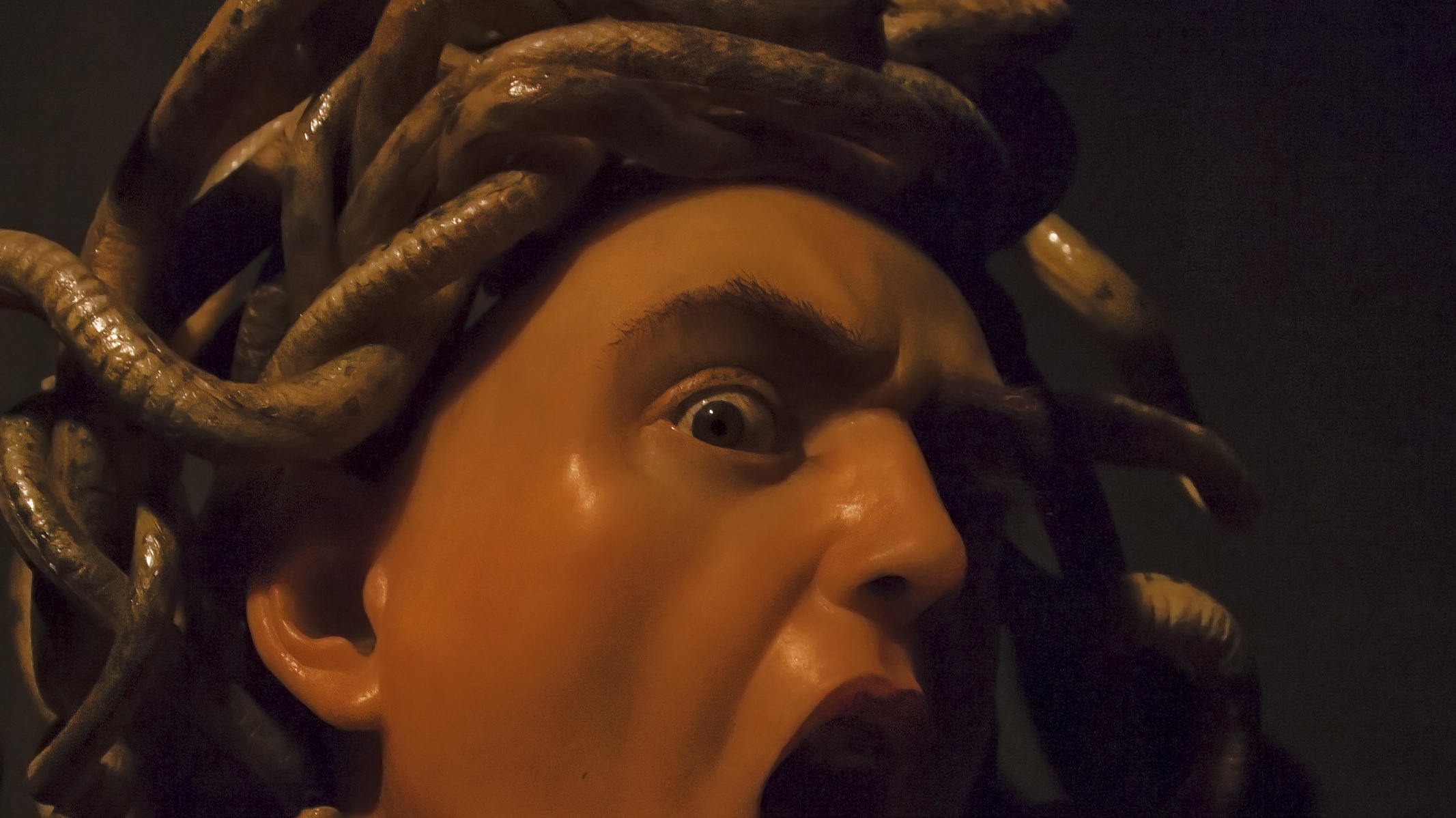

Hello bold adventurers and welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m your host Lucas Livingston. Back in episode 53, we explored the mythology and artistry of that demonness of Greek legend, the serpentine Gorgon Medusa. As foretold, we now delve deeper into her primal lair and confront her petrifying gaze as we closely examine a few salient works of ancient art exploring Medusa’s roots, influences, and evolutions.

A point I made in the previous discussion of Medusa was that she may not have been solely the creation of the Ancient Greeks, but that she was part of a vast inheritance of myths, religion, and imagery from the Ancient Near East and from the earlier Bronze Age Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. [1] It’s been suggested that the primordial Medusa could have derived from a snake goddess, a mistress of beasts, or perhaps a solar deity. [2] We previously compared Medusa to the Egyptian Eye of Horus and the Egyptian snake goddess, Wadjet. As part of Archaic Greece’s inheritance from its earlier Bronze Age civilization, could the famous Minoan Snake Goddess be the prototype for the figure of Medusa?

These faience figurines of the so-called Snake Goddess were excavated from the ruins of Knossos on the island of Crete by Sir Arthur Evans in 1903. There’s scant evidence about their true nature, but they’re certainly visually striking. They’re both a little over a foot tall and are dated to c. 1,600 BC. One seems almost enveloped by coiled serpents about her arms and torso, even slithering up her tall crown, perched like the cobra of the Egyptian uraeus (although, we should note that that part is a modern reconstruction by Evans). [3]

The other figurine grasps writhing serpents in her outstretched arms as if in some sort of ritual dance or chant. While neither figurine has writhing snakes for hair, it’s important to note that this feature of Medusa was a much later addition. As we already read last time in Hesiod’s Theogony, perhaps the earliest written account of Medusa, there’s no mention of snakes for hair.

Just a mere thousand years later than the Minoan figurines, but at least on the same island — Crete — we have a couple fragments from a 6th century BC temple showing the typical Archaic Greek example of the grimacing Medusa. We see recoiling snakes flanking her head, and on the surviving torso of one of fragments she grasps snakes in her clenched fists with a symmetry remarkably similar to the Minoan figurines. [2] That said, there’s no hard and fast evidence to support a connection between the Minoan figurines and Medusa beyond just visual similarities and geographic proximity. If you want to learn more about the Minoan Snake Goddess, there’s a great essay by Christopher Witcombe at arthistoryresources.net. And also, while it’s a little dated, check out the 1911 article “Medusa, Apollo, and the Great Mother” in the American Journal of Archaeology, volume 15, number 3. There’s a link to it ancientartpodcast.org/bibliography.

The grimacing Medusa makes her appearance throughout the Archaic Greek world. Way back in episode 5 of the Ancient Art Podcast on A Corinthian Pyxis in the Art Institute of Chicago, we were introduced to the sculptures from the pediment of the Temple to Artemis at Corfu just off the western coast of Greece. Built around 580 BC, this is the earliest known example of pedimental sculpture in Greece. The pediment is that large triangle above the entrance. Here we see Medusa with big bulging eyes and gaping mouth with lolling tongue. Tight curls of hair roll across her head ending with spitting vipers, and two thick serpents jut from behind her ears, swarming about her long braided locks cascading over her shoulders. Two more snakes are tied around her waist like a belt, facing each other similar to the grasped snakes from the contemporary temple fragment on Crete. In early examples it’s not uncommon to see Medusa in her entirety; not just as the disembodied head known as the aegis. And this Medusa is on the go, arms swinging and legs striding in the act of running. Flanking her are her two offspring, winged Pegasus and Chrysaor, who interestingly came into the world only upon Medusa’s beheading, but Greek art has a penchant for taking liberties with narrative chronology. If Medusa is thought to represent the wild mistress of beasts and feminine fury, as some have labeled her, it stands to reason here that she’d find herself decorating a temple to Artemis, the maiden goddess of the hunt, wilderness, animals, children, and childbirth. [4]

Jumping back about 70 years, one of the earliest representations of the Medusa and Perseus myth can be found on a tall painted vase from about 650 BC. Remember from last time that Perseus was the Greek hero, who beheaded Medusa. This is one of the more famous works of early Greek art known as the Polyphemus Amphora painted by … wait for it … the Polyphemus Painter. You also see it called the Eleusis Amphora, because that’s where it’s from. Most of the attention is showered on the grisly scene on the vase’s neck, the blinding of Polyphemus (from the Odyssey; totally unrelated here), but along the body we see a very early image of the ghastly Medusa, or more specifically her sisters, the other gorgons, Sthenno and Euryale, chasing after Perseus. We can sort of make out the legs of Perseus as he runs off through the reconstructed section. The goddess Athena stands strong between him and the gorgons. Swiveling it around, though, we see the crumpled, headless body of Medusa. It almost looks like she has a serpentine body instead of legs, but the dark section is actually a wrap tied around her waist, and she’s wearing a long skirt. You can just make out her little feet peaking out from the bottom of her skirt. The faces of Sthenno and Euryale are more mask-like than realistic faces—truly monstrous with huge, gaping, fanged mouths, protruding tongues, piercing eyes, and vicious draconian serpents writhing about their heads.

The geometric patterns on their chins almost seem to suggest beards. The bearded gorgon is not uncommon. The Nessos Amphora painted by, you guessed it, the Nessos Painter in c. 620-610 BC shows a similar scene of the gorgons giving chase to avenge the murder of their sister. But here we see bearded winged gorgons. The easy way to explain this is that the gorgon, as it evolved in Greek culture, became a pastiche of many ancient and foreign influences. The emerging Greek art, religion, and mythology adopted many Near Eastern and Egyptian concepts, including the already hodgepodge Egyptian god Bes, protector of the household, children, childbirth, and mothers, complete with grimace, beard, and sometimes tongue, wings, snakes, and all kinds of other attributes. He’s just a mess.

Perhaps my favorite examples of gorgons in Greek art are found decorating wide drinking cups, which look more like bowls to us. The kylix was a favorite type of cup in Greek drinking parties, which we already covered way way back in episode 3 of the podcast on the Donkey-headed Rhyton in the Art Institute of Chicago. We can imagine the surprise and chuckle shared by tipsy guests at an Ancient Greek symposium as you would tilt back your kylix to quaff your wine only to reveal the glaring gaze of a gorgon staring out at you from the bottom of your cup. If perhaps only for a brief second, you might worry if the gorgon’s piercing gaze will turn you to stone—perhaps a commentary on the dangers of drink. And on the underside of drinking cups we sometimes find two large glaring eyes, so-called “eye cups.” And this decoration is similarly connected with the gorgon Medusa. As the drinker lifts the kylix to his mouth, finishing his drink, he dons the monstrous mask of the gorgon. His friendly companions then witness his transformation from the good-natured symposiast to the glassy-eyed beast of alcohol’s domain.

Thanks for sharing the fun with me in our discovery of the creepy creature of chaos, the Gorgon Medusa.

Don’t forget you can “like” us on Facebook at facebook.com/ancientartpodcast and follow me on Twitter @lucaslivingston. You can subscribe to the podcast on YouTube, iTunes, and Vimeo, and be sure to give us a rating and leave you comments. You can also reach me at info@ancientartpodcast.org or use the online form at http://feedback.ancientartpodcast.org. As always, thanks for tuning in and see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2013 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[1] Gisela M. A. Richter, “A Bronze Relief of Medusa,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Mar., 1919), pp. 59-60.

[2] A. L. Frothingham, “Medusa Apollo and the Great Mother,” American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Jul. – Sep., 1911), pp. 349-377.

[3] Witcombe notes: “Large portions of the figurine seen today are reconstructions. Of the original figurine, only her torso, right arm, head, and her hat (except for a portion at the top) were found. It not at all clear, for example, that it is one single snake that has its head in her right hand and its tail in her left.” Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe, Women in the Aegean: Minoan Snake Goddess, 4. Evans’s “Snake Goddess.”

[4] Regarding Artemis’s role in childbirth

———————————————————

See the Photo Gallery for detailed photo credits.

Music:

Antonín Leopold Dvorák (1841-1904)

String Quartet No. 10 In E Flat, Op. 51

musopen.org

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Fantasie, Funeral March and Finale

(From Siegfried, The Ring of the Nibelung)

musopen.org

Nightshift

Brian Boyko

freepd.com

Additional media courtesy of:

American Journal of Archaeology (1911)

Apple Garageband

Wikimedia Commons:

Rama, George Groutas, Wolfgang Sauber, sailko, Dr.K., Marcus Cyron, Angela Monika Arnold

flickr:

Panegyrics of Granovetter (Sarah Murray), mari27454 (Marialba Italia)